How Curiosity Helps Children Build a Habit of Attention

The Boise aquarium was small. It boasted over 35,000 gallons of seawater, which may sound like a big number, but when you imagine dumping gallon after gallon of milk to fill up the tank holding sharks, rays, and pufferfish, you run out of gallons pretty quickly.

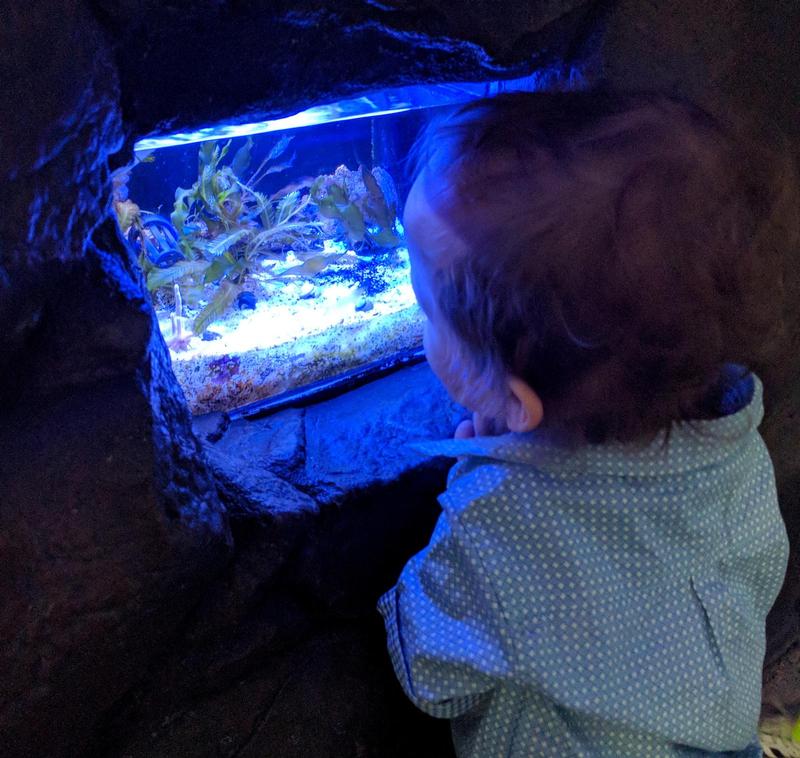

We were in Boise for a combo family trip and academic conference, nearly two years ago now. We wandered past backlit blue tanks filled with typical aquarium ecosystems: coral, rocks, colorful tropical fish, slick green weeds, the occasional sea anemone.

Most people walked through at a quick pace: twenty minutes. Half an hour, if you got a fish feeding demonstration or one of the staff brought out a snake coiled around her arm.

We spent three hours. At one point, nearly two hours in, a staff member came up to us, looking both alarmed and surprised: "You're still here?"

We spent so long exploring the little aquarium because our son Elian, who was two and a half years old at the time, wanted to look at everything. He stood with his face pressed to the glass, watching intently as fish swam up and down and around. A back corner of the aquarium housed a handful of leafy green enclosures. At one point, we spent a good fifteen minutes watching the chameleon slowly crawl along a branch. We weren't in a hurry to be somewhere else, to check "been to the aquarium!" off our vacation todo list, so Randy and I followed our son at his own pace.

The aquarium had one "hands on" tank for kids to gently prod sea stars and hermit crabs, and let skinny silver fish swim past their fingers. Adjacent was a table with a collection of seaside treasures to explore: rubbery seaweed, shells of different shapes and colors, shark teeth, a lobster's carapace. We lingered a long while as Elian carefully examined everything.

Later, we stood by the shark tank, watching their bodies curve past the glass. Elian was wide-eyed. Then some plump brown-haired middle schooler pushed in from the side. The kid was part of a school group, shepherded through the building by a couple wildly energetic and loud teachers, here for their annual field trip to see some fish. The kid ignored the presence of our toddler. He climbed right in front of Elian, leaning over the tank, and shouted about how he could see a shark and wouldn't it be cool if he could put his hand in the water and touch one (the sign said, no, don't do that, bad idea), and what was that thing swimming there? And then, just as fast, the kid lost interest—the sharks and rays swam away.

Patience for payoffs

That same trip to Boise, we also visited the Boise zoo. We paused by the tiger enclosure, looking through the fence to where the tiger lay, against the far wall under a tree, barely visible. I would have walked on—sleeping tiger, come back later—but Elian wanted to wait. Another family came up, peered at the distant tiger, left. Minutes passed. Then the tiger rose to its feet. It paced toward us—and padded right past the fence where we stood, giving our son a close-up view of the big cat. His patience had paid off.

Children, even very young children, have great capacity for sustained attention. More than most people think. The key is motivation. Children probably won't attend to whatever others want them to attend to… but left to their own devices, they'll stick with the things that interest them—tigers, fish, chameleons.

Another thing that struck me about these incidents was what counted as exciting. Most people wouldn't find a sleeping tiger exciting, or a creeping chameleon, or fish swimming in circles. Exciting is usually action-packed, sharks tearing other fish to pieces, an immediate reward for the price of admission. I think this difference reflects whether children have internalized an expectation that others should entertain them, versus being responsible for their own play and their own engagement in the world.

School groups don't let kids engage

In the zoo, we were passed by school group after school group. The kids, varying from elementary grades through middle school, wanted to explore. Sometimes we saw a kid trying to linger, to watch the llamas ears twitch one more time, or a lemur to leap up onto another branch. But these children were inevitably pulled along. Their natural curiosity about the world was stifled—have to "get through" the whole zoo, line up, don't run, fill out the worksheet (check the boxes: yes, saw that lemurs exist behind glass, didn't see what they do, how they act, whether they play), raise your hand to talk (we're outside, not in a classroom?), hurry to the next exhibit. No time to waste being curious!

Part of the problem, I'm sure, is the structure inherent in the school field trip. When you have a few teachers trying not to lose any of the kids in their large group, of course there will be a limit to how long you can stay at an exhibit. But instead of saying "better see some zoo quickly than none at all," perhaps we ought to go in another direction: we don't have to keep the system. Children need to explore. Once their curiosity is stifled, can you get it back? Schools, and school field trips, don't have to be the default.

Child-led exploration leads to sustained attention

One of our weekly activities is a nature-focused "forest school" group. We meet at parks—out in the woods, not at playgrounds. We find semi-wild places for our children to explore. Most of the kids are young still, preschool-age or younger. The children climb rocks, count how many colors of wildflowers they can find in spring, play hide and seek in the bushes.

One of the core tenants of this group is to let children be children. We sometimes have group activities—reading books about nature, doing leaf rubbings with crayons, collecting fallen leaves to make fall crowns, planting seeds—but children aren't forced to participate. If they would rather use a magnifying glass to watch the first ladybugs of spring crawl out of hibernation than listen to the book, or climb a tree instead of sitting still, we let them.

When children are encouraged to explore and engage at their own pace in the natural world, they readily do so. They are born wanting to understand the world around them! They are born curious. If you support their curiosity, the results, as they say, will surprise you.

Building a habit of deep attention

Supporting children's natural curiosity helps them build the habit of sustained attention. Habits are built over time, through practice. Attention is a habit we can practice. Have you ever felt you can no longer sit down to read an entire book, because you're too used to consuming information in screen-sized tidbits as you scroll? You've formed a habit of broken attention. Letting children dive deep and engage deeply in their everyday life lets them practice sustained attention, instead.

Tigers and fish.

Follow your children's passions and interests. Sure, there may be subjects you think they ought to learn, and there's room for that. But especially when they're young, give them time and space to engage deeply. Practice attention. If they want to spend an hour watching sharks circle, well, why not? That's why you visited the aquarium in the first place, wasn't it?

A Strategy for Developing Antifragile Finances