The Nebulosity of Categories and Where the Usefulness of Personal Labels Ends

Not crashing was rewarded

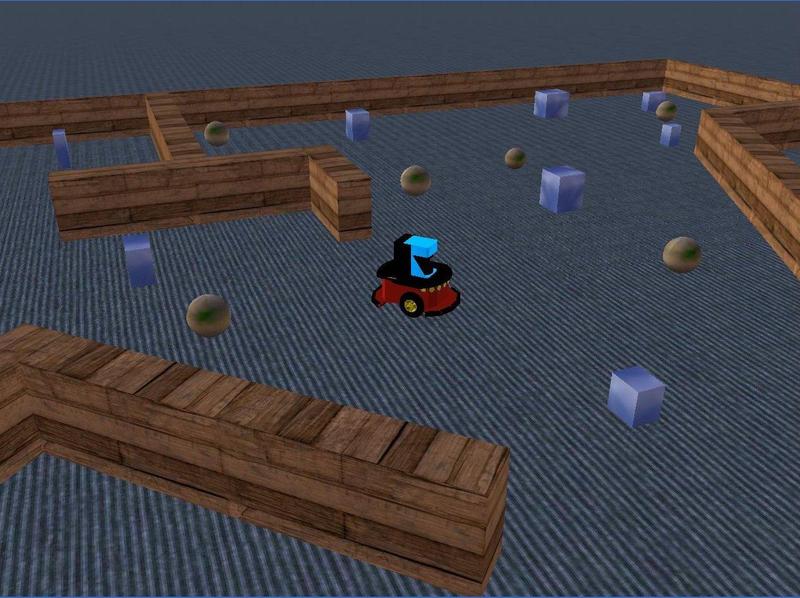

Drive, little animated robot. Blocky wheels spinning, the robot crashed into a virtual wall. Bump. It paused. Slowly backed up. Turned a little to the left. Then it drove forward again—straight for the next section of wall—completing its lame attempt at navigating the maze I had programmed for it. Bump.

In the summer of 2008, I worked in an overly air-conditioned, windowless cement bunker, which I note because of the contrast with the great outdoors. Outside it averaged approximately 95 degrees and boasted a humidity level equal to an unventilated bathroom after a hot shower. Every day, I carried a sweatshirt across Vassar's muggy campus, so I wouldn't freeze in the chilly depths of Olmsted Hall.

Every day, I punched in the door code (a secret sequence of four or five numbers that I've since forgotten), pushed open the heavy black door, and pulled up a swivel chair at one of the workstations along the wall. The decor was classic robotics laboratory: White boards with half-erased software architecture diagrams. Shelves of electronics, mechanical parts, and cardboard boxes labeled in Sharpie. A couple Lego Mindstorms kits. Extra monitors and cables. A golf cart, waiting for its day to drive autonomously around campus. Among the clutter, I hunkered down in my sweatshirt with laptop and desktop side by side.

The goal was straightforward. A little mobile robot needed to learn to navigate. My project was to help it learn whether to drive straight, turn left, or right, or back up using a predictive neural network. The robot would drive around, look at things with its sensors, bump into those things, and supposedly learn about the consequences of its actions—thus learning to stop and turn before its sensors said it was bumping into something.

The project was led by my professor Ken Livingston alongside upperclassman Josh de Leeuw (who is now a Vassar professor as well). While their key insight was how adaptive learning depends on the ability to make good predictions, the part of the project that stuck with me more was how the little robot attempted to form categories.

The robot had a bunch of sensor data. In order to learn to navigate, the robot had to learn how to divide up that sensor data into useful “bins” of information, which fed into its neural network, which then predicted whether or not it was going to crash. (Not crashing was rewarded.) “Binning” the data into useful categories meant the robot could predict better, and would therefore be less likely to crash.

Nebulosity and boundaries

Category formation is an interesting puzzle because its solution depends on context. At the broadest level, category formation is how an organism or agent takes perceptual input from the world and chunks that input into things. Where the boundaries are and what belongs in a category is a question of what makes something similar to something else, how similar two things have to be to belong in the same category, and which dimensions of similarity are relevant for the task at hand.

Many people think of categories as being either-or. I was in the chilly basement robotics lab, or I was in the humid outdoors. A thing is within the boundary of a category, or not. The label—the name of a category—applies, or it doesn't. This is the classic ontological problem.

But if you look closely, most categories—all categories?—have fuzzy edges. If you stand on the threshold of the open doorway, feeling both the cool interior air and the sticky, pre-thunderstorm heat, are you inside or out?

Categories are like clouds. Imagine a puffy, marshmallow cumulus cloud, floating up in a big blue sunny sky. Where are its edges? Keep watching the cloud. It may change shape. It may dissipate. If you fly up to it (on your… hovercraft...), you'll find yourself in the midst of fog. Where did the cloud begin? Where does it end?

The cloud is real, no doubt there. But it is nebulous. (A term I first saw applied to categories in David Chapman's Meaningness book). Categories are like clouds: nebulous. The boundaries, where you begin wondering whether a label applies, whether you're inside or out, are indistinct.

Labels are tools for understanding

Our About page currently states that I am "a homeschooled, category-defying lifelong learner."

Fun fact: Even deciding which labels to list in that sentence was tricky! It's not that I'm anti-label or that I don't fit in any categories. It's more that eschewing strict labels goes hand-in-hand with how I view identity.

A label implies belonging to a category. For example, yes, I was homeschooled. But that is not all... So the label is true ... but if we are grouping along another dimension of similarity, if we are looking at different categories, then the dimension “was homeschooled” may not be relevant, or may even preclude belonging in another category ... even if belonging in that other category is also true of me. For example, I currently hold a mix of conservative, liberal, and libertarian political ideals, depending on the issue and level of government we're talking about—which of these labels should I use? And when?

Categories overlap. Which labels I list in a bio depends on which facets of myself I want to emphasize. Which facets are relevant. For the purposes of this blog, since it is about my life in general, pretty much anything I listed would be relevant, and at the same not encompass everything that I might touch on in future blog posts. So I picked some words that seemed pretty general.

Any given label cannot describe the whole of me. A quote from a favorite book:

Words do not contain or define any person. A heart can, if it is willing. (Golden Fool, Robin Hobb, pg.402)

Labels are tools for understanding. They are descriptive, not prescriptive. Language is imperfect, and the fuzzy categories we have reflect the generalizations language necessarily makes... and so labels, and categories, cease being useful when they cease helping us describe and understand our experience.

Identity is multifaceted

My identity has frequently been made up of overlapping elements, with membership in multiple categories. Unlike Randy, who is happy with “trad Catholic” being his primary label, I don't have one aspect of myself that I identify with most strongly. Nor do I expect my identity to be entirely encompassed by a set of imperfect labels for nebulous categories.

For example, in college, my social circles included the fencing team, a nerdy board game and RPG group, my cognitive science/academic group, and some folks in the campus circus troupe… unlike many, I did not primarily identify with one group more than the others. My fencing team identity was as central as my academic self or my board game self.

I remember one time, I showed up for a board game night in workout gear—perfectly natural to me, comfortable, the kind of thing I might wear to a fencing practice. And one friend asked, “Are you okay?” Because he'd never seen me wear something so casual. Clearly something was wrong. (I had a habit of dressing reasonably nicely outside of practice.) But I was surprised by the question. I hadn't noticed the incongruity before—that my social circles could have such separate components, despite both feeling completely normal to me.

I think problems can arise when people forget that identity is multifaceted. Elevating one aspect of oneself over the rest all the time pushes us in the direction of tribalism; in-group versus out-group. When you identify so strongly with one group (one label, one category), all other groups are all deemed the enemy.

I've read some of the psychology research on this topic. A few studies showed that even something as innocuous as wearing green versus red armbands could influence people's feelings of group belonging. People behaved more favorably toward same-color-armband-wearers (and less favorably toward opposite-color-wearers) for no other reason than that. When the groups in question have some weight, such as those reflecting religious, political, and philosophical differences, the divisions created may be stronger, and may hold less room for flexibility and dialogue.

Flexibility is part of the appeal of keeping my identity unrooted, so to speak. I understand Randy's attachment to the "trad Catholic" label. He wants that aspect of himself to pervade the rest of his behavior, so he spotlights it when thinking about his identity. But in my case, there is not one such aspect. I'm reminded of a post of David Chapman's from a while back, in which he discusses his bemusement at other people's strong opinions on things they know little about, such as preferring paper bags to plastic bags:

So why do some seem so sure? Because paper-versus-plastic is a way of proving that they belong to a particular social group, and that they are good people according to the standard of that group. As with so much in Buddhism, it comes down to anxiety about anatman—the fact that we do not exist in any definite way. We insist on the right kind of bag to prove that we are that kind of person. We demand paper (or plastic) to be accepted by a particular group. Being a member of the group defines us—as a member—and thereby proves that we do actually exist...

[In Buddhism,] Recognizing that I am not any particular sort of person is one of the most important aspects of the path.

Which labels are most relevant and which I use depend on the context. Some are more dominant at some points in time than others. This allows me flexibility, keeps room open for true dialogue, and holds space for change (and change is a constant).

How We Live Debt-Free in a World of Chronic Debt