America Needs Strong Towns and Community, Not More Infrastructure

At TEDx Couer d'Alene in January 2020, Blair Williams shared how she helped a small Montana town revitalize its downtown—going from 87% vacant lots to just 13% vacant lots—by setting out chairs.

That's right. Chairs.

Putting adirondack chairs along the sidewalk led to increased foot traffic. People stopped to rest and chat. Local musicians and artists set up along the street. People began seeing the area as valuable again—as a public space where they could be. It was brilliant.

Little actions can have big payouts

With the current pandemic-induced economic shutdowns and recessions, I think we're going to need more people like Williams in the near future. We're going to need new, creative ways to rebuild our towns and our economy. But, as Williams's creative placemaking showed, the actions we take in rebuilding don't have to be big or government-imposed. Small actions and little investments can have huge payoffs.

Small, local, iterative investments is the big idea in Charles L. Marohn, Jr.'s recent book Strong Towns: A Bottom-Up Revolution to Rebuild American Prosperity. I reviewed Strong Towns for Erraticus Magazine earlier this year. As I wrote there:

Investing in small things that fix problems for people right now can turn a block around. Citizens become partners in the transformation. In a myriad of ways, small actions can improve social connection and financial productivity in our places of being.

The root of the current problem is that, as Marohn explains in the first few chapters,

Engineers are generally trained to see cities as "a collection of roads, streets, pipes, pumps, valves, and meters," asserts Marohn. Cities are considered complicated but ultimately predictable machines. And thus, city planning is reduced to zoning. Cities are not allowed to evolve naturally.

Marohn argues that we are fooling ourselves if we think can simplify the complexity, interdependence, and interrelations of a human city into a model that follows straightforward, mechanical rules...

Perturb a complex, adaptive system, and it will change, becoming more resilient. Perturb a fragile, complicated machine, and it will break. If we treat cities like complicated machines, when change comes along, the cities will break.

Instead, we need to allow cities to adapt, using what Marohn calls "little bets" to improve iteratively.

[Marohn is] a proponent of subsidiarity—the idea that problems should be solved at as local a level as can actually solve them. Local problems, local solutions. His advocacy for Strong Towns rests on the ability of complex systems to learn and adapt.

Imagine a company making a new product. They test it out with users. They ask for feedback. They observe where users have problems. They tweak the product. Test it again. Get more feedback. Observe more. This iterative, human-centered cycle of development is the kind of collaborative, iterative approach Marohn says will work for towns. In short, you have to deeply understand people's experiences and daily lives to know where the pain points are and to see what small changes might improve things.

Read the whole review!

Economic implications: The world is a complex system

How does Strong Towns apply to the city I live in and my own life? Many of the book's messages resonate with ideas Randy and I had been discussing for the past couple years: How to build community. The role of religion in community. The role of place, neighborhood, family. How so much is local. And also, how our social networks extend beyond the local in ways they couldn't at prior points in history.

Recently, given the global pandemic situation and the effects lockdowns have had on local and global economies, I've been wondering about the implications the book has for our economic policy as a whole. While this is speculation that I haven't fully fleshed out, I see parallels between Marohn's list of city-level problems (such as a lack of systems thinking in urban development) and the problems we have at larger scales—like the recession and pandemic response being related to people not treating the world as the complex system it is.

I also see parallels in investment strategies. The common pattern is this: Borrow money from the future to finance projects now. Depend on growth and increasing prosperity to pay off debts. And hey, it can work. If you get economic growth, you're free and clear. But Strong Towns criticizes that model, arguing that we can't rely on continuous growth, because... well, the book leaves it there. Because growth always slows, no citations. Marohn argues that cities should be stable without needing growth (seems reasonable), but doesn't adequately explain why growth cannot continue indefinitely.

I'm wondering about this investment pattern because it's what the federal government does, too, only on a larger scale. The government takes on debt to fund economic growth and relies on the GDP growing every year. Some portion of national debt is interest payments. So long as that interest portion of national debt doesn't grow, while GDP does, then I guess the idea is eventually, the debt could be paid off by the growth.

However, in general, we'd say doing something like taking out a loan to invest in the stock market is a bad idea, because it doesn't account for risk (e.g., the market may crash). But arguably, the government may not need to worry about risk as much, because it's investing in a wider range of areas—the same way a mutual fund decreases risk by putting money into a variety of stocks instead of going all in on just one company.

I'm wondering whether the government ought to be relying on continuous growth, the way cities seem to ... the way Marohn says they shouldn't. How does this all play out at the national level? A nation is just as much a complex system as a town is. But perhaps nations are different; they are the money issuers, rather than money users who can get into too much debt; Modern Monetary Theory argues there is no such thing as too much national debt (instead, national debt represents money the government put into the economy and didn't get back in taxes). This raises interesting questions about the roles of growth and debt at the national level. I haven't read enough about the theory to decide whether it's credible, though I admit I'm skeptical.

Perhaps we need more people making decisions who understand complex systems and see the world, nations, and towns as complex systems. We need people with the humility to know that they can't foresee all possible effects of actions, and probably can't know with certainty whether any decision was the "best" one or the "right" one, because things are interdependent in a complex way. Second order effects. Third order effects. Predicting how different parts of a system may react to any given perturbation is hard. Sometimes, impossible.

Anyway, my PhD is not in economics. I do think towns ought to heed Marohn's advice in coming years. But I wonder about federal policies. If you have book recs for me on this topic, or thoughts you'd like to share, I'd love to hear them!

Building our own strong towns?

So what's next? How do we start making our towns stronger? My biggest quibble with Strong Towns was a lack of a clear next step for individuals.

As a concerned citizen, if I want my town to be a strong town, what can I do today? Do I need to read up on my city's budget report? (I did look it up and scan through it.) Do I need to start attending city council meetings and argue for repealing regulations? Initiate a new neighborhood potluck, turn my yard into a playground for local kids, read up on tactical urbanism and the Better Block Foundations' placemaking?

Reflecting more since writing that review, one way to start is small—at home, with our own yard. After all, home is where we first implement many changes we want to see in the world.

This year, Randy and I are embarking on our second major yard improvement project. Our first project, when we moved in to our house, was to add raised garden beds. Now, we're pulling out the ugly evergreens that fenced in our front lawn and replacing them with a picket fence and nice landscaping. Those trees had to be trimmed in such an awkward way to not encroach on the sidewalk!

Perhaps something as simple as improving our house's curb appeal will have an effect on our neighborhood. Marohn seems to think it would: It shows our neighbors that we're invested in our property. It could inspire them to work on their own yards too, thus increasing the value of the whole neighborhood.

I wonder what else I should be doing. My city is actively and rapidly growing in ways Marohn would say are unsustainable. How else can I make a difference? (Maybe I should mail copies of Strong Towns to all my city council members...)

I saw an article a while back with 101 ideas for improving your city. Some make little sense where I live, but some were cool. Like these:

- Guerilla gardens and seed bombs. Plant in vacant lots and untendered land. Throw flower seeds at hard to reach areas.

- Fix up your porch. Add flowers. It can brighten the area and inspire others to do the same. I always love the houses with bright flowers out front!

- Build a pop up playground. I like the idea of giving people more opportunities to play!

- Plant an urban orchard, like fruit trees in cities (e.g. this orchard project in Chicago). I love functional plants that are both decorative and useful.

- Map your public produce and make sure free food doesn't go to waste. For example, Fallen Fruit plants fruit trees and makes art; rescues and donates produce. Last year, we picked large yellow crabapples off a public tree and made apple butter.

Evidently, I have a soft spot for growing things. What ideas do you have? Do share!

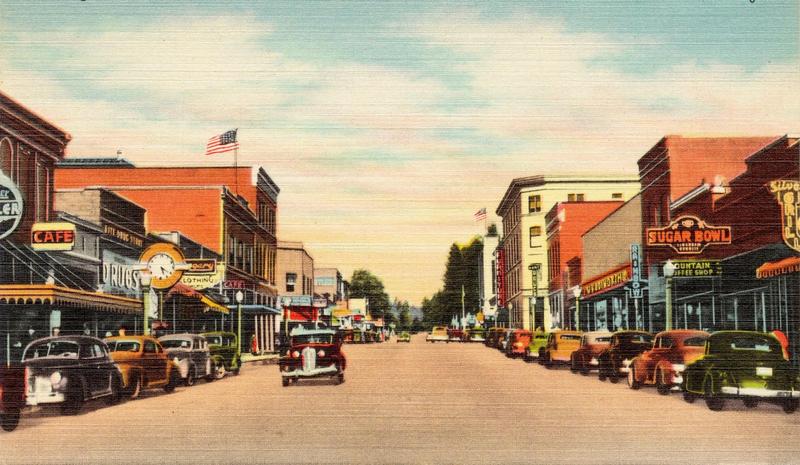

Credit for this post's header image: Tichnor Brothers, Publisher / Public domain

How We Are Intentionally Building Strong Community Ties