Book Review: The Expectation Effect: How Your Mindset Can Change Your World by David Robson

"While many of today's crises are beyond our control, our responses to difficult situations are often the product of our expectations—and understanding this allows us to increase our resilience and to react in the most constructive way to the problems we face."

Why do expectations matter?

We all have expectations. We think particular things; we hold particular beliefs. Robson argues that our thoughts and beliefs affect what happens to us. Our thoughts and beliefs—our expectations—have real-world consequences. Thoughts and beliefs are not just "what's in our heads" because what's in our heads can influence health, sleep, stress, memory, concentration, fatigue, creativity, and more.

The Expectation Effect: How Your Mindset Can Change Your World by David Robson (Henry Holt and Co, 2022) is about the power of expectations. This book isn't about optimism and positive thinking—though Robson does explore our expectations about emotions. It's a dive into specific instances where what you think and how you approach a situation can significantly affect the outcome, backed up by research. Every chapter ends with a useful list of ways to apply the insights of the chapter.

I'd encountered some of this research before, but there was plenty of new stuff, too, which was awesome. I love the kinds of studies that are used to study expectations. Often, participants are given the same experience, but are told different stories about it—which means they form different expectations. Any difference in outcomes between participants can be attributed to their expectations.

How can expectations affect real outcomes?

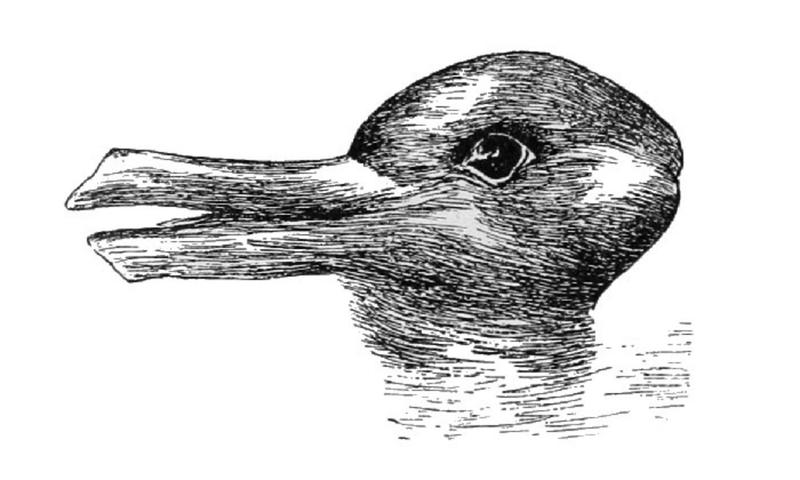

Here's a simple example. See the figure below? What do you think it is?

Some researchers did a study with this ambiguous figure. They asked zoo visitors to report what they saw. Ninety percent said it was a bird looking to the left. At Easter, only twenty percent said it was a bird! Far more thought it was a rabbit!

This example shows that our expectations can affect our perception of a real, if ambiguous, line drawing. If you're primed to think about bunnies at Easter, you're more likely to see the rabbit in the drawing.

Robson explains that our brains are constantly trying to predict what's going to happen to us so that our bodies can be prepared to deal with it. Your brain uses all the relevant context it can—like the fact that the Easter season often includes bunny motifs—to predict what you're going to encounter in the world. Robson writes,

Before you walk into a room, your brain has already built many simulations of what might be there, which it then compares with what it actually encounters. At some points, the predictions may need retuning to better fit the data from the retina; at others, the brain's confidence in its predictions may be so strong that it chooses to discount some signals while accentuating others. Over numerous repetitions of this process, the brain arrives at a "best guess" of the scene."

What you see in the world, then, isn't necessarily what's actually there. It's your brain's best guess.

Robson writes that this is a new theory, but it's not that new. Cognitive scientists have known that brains are "prediction machines" for decades. I read the book On Intelligence by Jeff Hawkisn and Sandra Blakeslee (Owl Books, 2004) in my first Introduction to Cognitive Science class in college, and I doubt that was the first place the idea of brains as predictors was presented.

Anyway, there were some great examples about the false images brains can produce, and how our top-down mental models and predictions about what we might see affect what we actually perceive, bottom-up, from our senses. The duck-rabbit study was one example. In another study, people were down a screen of random noise, just gray dots. But people could be primed to see faces in the noise up to a third of the time anyway. In other domains, people have strong expectations about the taste of expensive versus cheap wine, or about the effectiveness of designer versus cheap sunglasses.

Placebo effects

After describing some of these perception effects, Robson dove into the most well-known expectation effects: the placebo effect in medicine. The placebo effect occurs when people believe they're getting a treatment but are actually getting sugar pills (or some other fake treatment that has the appearance of the real thing), and then they actually experience the treatment they're not getting. They get the benefits, but also, often, the treatment's expected side effects (a nocebo effect).

Some of these effects were wild. For instance, early work found that saline injection of a "pain killer" helped soldiers before surgery, almost 90% as effective as the real thing. It is fascinating that our expectations can change our health, physiology, and pain perception—it seems like that shouldn't happen! But it does, and Robson explores some potential mechanisms. One reason placebo effects occur may be because receiving a placebo is a signal that you're being cared for, which can lower your fear and anxiety, so your body may lower inflammation and stress responses, allowing the next stage of healing to begin.

But here's the weirdest thing about placebos:

Open-label placebos have now proven successful in the treatment of a number of other conditions, including migraine, irritable bowel syndrome, depression, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and menopausal hot flashes.

That means that people who are prescribed a placebo, and know that they are prescribed a placebo, still get benefits from taking a pill. Even when they know the pill is doing nothing. Isn't that weird?

Robson also explains nocebo effects, which occur when we believe our body to be under threat. Instead of a positive outcome, nocebo effects exacerbate the negative.

Here's a simple example of a nocebo effect:

How often does a doctor or nurse warn that "this may hurt" before giving an injection or taking a blood sample? The thinking behind these words may be that it is best to allow the patient to steal themselves for the pain. In reality the short statement will make that pain more likely.

I wonder if this is why when getting blood drawn, the phlebotomist has said to me, "you will feel a small pinch." Is this how they are now trained to help set expectations about the amount of pain you might feel?

The weirdest result from this chapter is that nocebo effects can be spread through social contagion. That is, when someone near you shows negative symptoms, you're more likely to begin experiencing the same symptoms, because your brain may start to simulate those feelings. These simulations could feed into your brain's prediction machine, creating or amplifying a nocebo effect.

Other expectation topics covered

The later chapters cover a range of topics. Exercise—how exhaustion works, the benefits of reappraisal techniques, the power of visualization. Food, and how our beliefs about calories consumed affect satiety, metabolism, and nutrient absorption.Why viewing stressful events as challenges rather than threats improves outcomes, and how recognizing the value of negative emotions can lead to improved performance in all kinds of tasks, games, and sports. Why thinking that you are a bad sleeper and complaining about it (even if you are actually a good sleeper) leads to more negative symptoms such as fatigue and poor concentration than actually being a bad sleeper, but not realizing it. Why willpower isn't actually a limited resource and how you can tap into your mental resources. How to increase your intelligence—or rather, how your beliefs (and your teacher's beliefs) about your potential can cause you to succeed, or fail.

Here's a taste from the stress chapter:

When faced with a difficult challenge, people who see stress as enhancing tend to focus more on the positive elements of a scene (such as the smiling faces in a crowded room) rather than dwelling on potential signs of threat or hostility. They also become more proactive—deliberately seeking feedback and searching for constructive ways to cope, rather than trying to hide away from the problems at hand. They even demonstrate more creativity. All these changes would mean that they are better equipped to find permanent solutions to the challenges that were causing the distress in the first place.

Expectations are everywhere

I was fascinated by just how much is affected by our outlook. The Expectation Effect really highlights how much our experience is shaped by our own psychology and consciousness. All those famous quotes have it right: we make our own reality. Perhaps more so than most of us realize.

I wish Robson had spent more time exploring the mechanisms behind expectation effects. Most of the book focuses on that they occur and how we can use them to our advantage, which is probably what most readers want to learn. Personally, I'd like to know: how exactly do our predictions and expectations change our physiology? Robson explained some of the effects, mostly nocebo effects, through stress responses and chronic inflammation, but that can't account for everything. What else is going on?

Read this book if you want to better understand how your own mind works; if you want tricks for improving health, wellness, sleep, concentration, and more; or if you're generally interested in human psychology and the science of human behavior!

Five Board Games We Play With Our 6-year-old to Learn Math