Book Review: Get It Done: Surprising Lessons from the Science of Motivation by Ayelet Fishbach

"So how do you motivate yourself? The short answer is by changing your circumstances."

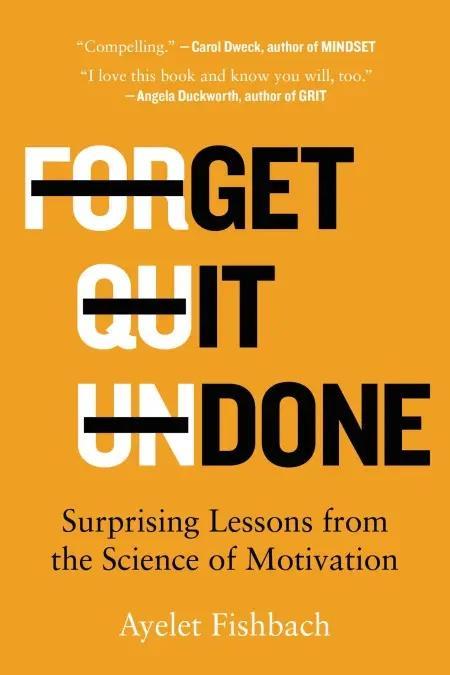

If you're interested in how motivation works and how to motivate yourself better, Get It Done: Surprising Lessons from the Science of Motivation by Ayelet Fishbach (Little, Brown Spark, 2022) will be right up your alley. Informative, practical, and based on decades of research, Fishbach covers all aspects of achieving goals. She explains how to pick the right goals, sustain motivation through the long haul, juggle multiple goals (since you will have many!), and leverage social support on your journey.

At its core, Get It Done is a guide to behavior change. If you want to achieve goals that, Fishbach assumes, you are not currently achieving, then you need to act differently. Some of the changes may involve internal circumstances, such as changing your mental image of a goal or your framing of the work you do, and some may involve external circumstances, such as adjusting which actions are available as options to you.

Fishbach presents a four-step process for changing behavior, with sections in the book devoted to each:

- Picking goals

- Sustaining motivation

- Juggling multiple goals

- Leveraging social support

Picking goals

If you want to achieve your goals, set reasonable goals. Many people set goals that are too abstract ("be happier"), too negative ("stop being addicted to social media"), or too vague ("get fit"). Instead, goals need to be linked to your purpose and your values—ask "why this goal?" for each goal you set. Then provide an answer.

Achievable goals are framed positively, as a behavior to do, rather than as the avoidance or suppression of a behavior (which is harder). When I was a fencer, my coach explained how we should encourage our teammates from the side of the strip in a similar way: shout "Keep going!" rather than "Don't stop!"—because for the latter, they'll only hear "stop!"

Goals should also be specific and quantifiable—you need to know whether or not you've achieved the goal. There needs to be a chance of failure. E.g., "Exercise 20 minutes a day" or "bench 250lbs" are better than "get fit". Give your goals target numbers or target timelines to make it easier to monitor and evaluate your progress. For instance, when I began daily writing, I aimed for 200 words a day. That's an easily measurable, easily trackable, actionable goal that's small enough to seem doable.

Consider whether goals are "ought" goals—i.e., things you need to do—versus "ideal" goals—things you aspire to do, but aren't strictly necessary. Ideal goals are easier to frame as approach goals. Ideal goals are also more likely to tap into your intrinsic motivation. (Read more about intrinsic motivation!) In addition, set your own goals. If you set the goal, then you have at least some amount of motivation toward achieving it!

I felt much of this section was straightforward and not revelatory, but I've read a lot about motivation science.

(Read: How I Manage Deadlines: 5 Ways to Keep Projects On Track)

Sustaining motivation

People are most enthusiastic about working toward a goal at the beginning and end of pursuing it—when they're energized by the newness and excitement of the goal, and when they're finally close to achievement. In between is the dangerous long middle. Motivation lags; you can see you've accomplished some, but not enough; there's still so much to do to reach the goal…

Some of Fishbach's chapters on sustaining motivation and the dynamics of goal motivation got a bit technical. The gist is, there are lots of strategies you can use to increase your motivation—and sometimes opposing strategies will work at different times and for different goals. Fishbach acknowledges that your feelings about progress and goals can be complex. Sometimes,

"feeling good about our progress increases our motivation; at other times, feeling bad about lack of progress pushes us to work harder."

Your feelings of commitment to a goal can affect the strategies you should use to encourage yourself to make more progress. Sometimes, looking back at your progress can increase your belief that what you're waiting for is valuable and worth staying for. Monitoring how far you've come may make you feel more committed to stay in the course. But other times,

"When you find yourself facing a goal that's highly important, framing your progress based on what you haven't yet accomplished may be more motivating than thinking about what you've already done."

Some of her suggestions felt like commonsense. For example, break goals into sub-goals. Break large projects into weekly assignments so you don't lose steam midway through. Set milestones, so you're always at the beginning of a new milestone or close to reaching the next one—minimize time that's just "in the middle".

(Read: How to Procrastinate Less by Increasing Your Motivation and Decreasing Temptations)

Leveraging intrinsic motivation for goals

One way to sustain motivation is to pursue activities that feel like ends in themselves—activities you're intrinsically motivated to do for the sake of doing them, that are fun or enjoyable or exciting. For these activities, Fishbach says,

"there is a perceptual fusion between the intrinsic activity and its purpose."

You're more likely to stick to a goal if pursuing it feels like achieving a goal rather than a step toward achieving a goal. For instance, if you want to improve your fitness to be healthier and have more energy, you may discover that you feel energized after a workout. That, in turn, makes working out more immediately rewarding and feel like you're achieving your goal even as you're pursuing it.

Using incentives to sustain motivation

You can use incentives and rewards to help maintain motivation. But incentives can be tricky: You have to use the right incentives to reward the right actions. If you reward the wrong behavior, you'll get more of the wrong actions. Plus, using external reward systems can decrease intrinsic motivation for a task. (Read more about intrinsic motivation!)

Fishbach argues that intrinsic motivation is decreased by extrinsic rewards because of how goals and activities are associated. At first, the goal of intrinsically motivated activities may be enjoyment or self-expression. When you add the reward, the activity becomes associated with getting the reward as well—a second goal. Fishbach argues that having multiple goals associated with an activity dilutes the importance of the activity in working toward the goal. She writes,

"[T]he more goals … a single activity serves, the more weakly we associate the activity with our central goal and the less instrumental the activity seems for the school. Therefore, our central goal is less likely to come to mind when we pursue the activity. And when a goal doesn't come to mind, the activity doesn't seem to serve the goal."

She argues, essentially, that activities associated with goals are a zero-sum game. I don't see why that must be the case—why can't an activity be associated with two goals and be equally important for both? Maybe that would work for two intrinsically motivated goals? I wasn't entirely satisfied with her explanation.

Fishbach also suggests that incentives will undermine children's intrinsic motivation more so than adults', because children are still figuring out which things they're doing because they enjoy them versus because of some other incentive. That seems plausible enough.

(Related: How to Build Self-Discipline: Why Awareness and Intrinsic Motivation are Key)

Dealing with setbacks

Negative feedback on your way to a goal can be a big setback. However, learning from error is important for growth! It's harder than learning from positive feedback, since if you do something right, you simply have to do it again to continue your success. Fishbach has numerous suggestions.

First, reflect on the unique information you just acquired. Ask whether you feel you haven't made progress. Remind yourself that you have. Try to keep an adaptive mindset that emphasizes growth and the need for feedback for growth. Distance yourself from the failure by imagining it happened to a stranger—and then ask what they may have learned from it. Give advice to someone with a similar issue.

Goal juggling

You're not going to have just one goal, which means you will inevitably attempt to juggle goals. Fishbach shares different goal systems and ways of categorizing goals. For instance, you might categorize goals into the categories social connection, wealth, and health. Then, you might sub-categorize goals among those categories: finding a spouse, finishing a degree, getting a promotion, meeting exercise goals, and so on.

The problems come in when you have two goals in conflict—for instance, eating healthy by only buying organic food, and also staying on budget. Fishbach relates two strategies: First, compromise. You might make progress on all fronts but not satisfy anything completely. Second, prioritize one goal at the cost of the other. She says we tend to compromise when we feel like we've made some amount of sufficient progress. We prioritize when we feel our actions need to express commitment to the goal, when we want our actions to reflect who we are as people, and when we think our actions say something about our identity. Compromising in this case would send a mixed message.

Fishbach includes chapters about self-control and patience. Her strategies for increasing self-control and managing temptations were fantastic, and I've included many in my article explaining ways to procrastinate less. In short, self-control is a two-step process: detect or become aware of temptations, and then battle them. Fishbach writes,

"Self-control strategies counteract temptation, canceling out the influence of temptations on your goal. This works either by increasing your motivation to adhere to the goal or decreasing your motivation to give in to temptation."

(Related: The Power of Waking Up Early: Nine Tips for Becoming an Early Riser.)

Social support

"Social isolation is so unnatural to humans that it's considered a harsh and often cruel and unethical punishment."

Fishbach argues that it's easier to bond with people who share your goals, or who you feel support your goals. You gravitate towards people who share the same goals as you and encourage you to stick to what you want. Pursuing a shared goal can make you feel deeply connected to someone. Holding goals for others, such as helping them succeed in a new job or wanting them to complete a marathon, can also engender connection. Even mundane goals and activities can build connection, such as shared books, food, or hobbies. As Fishbach says,

"We move toward and away from people as we prioritize or deeper towards the goals they can help us achieve. When it's the right time to attend to a goal or when we feel we're falling behind, a goal gets high motivational priority. As a result, we draw closer to those who are instrumental to achieving it. Once the goal has sufficiently progressed and its motivational priority reduces, we feel less close to those people."

One concept Fishbach discussed that I thought was cool was the concept of self-other overlap, i.e., the perception of a psychological overlapping between ourselves and others. People often conform to the group. You often internalize the views and goals of the people around you because they're part of you. This is why role models are so important:

"Role models are important figures in your life for your model is selling to whom you feel close into this place of qualities you'd like to see in yourself. ... you feel you have somewhat overlapping identities. You could potentially be like them, so they inspire you."

Fishbach explains scenarios where people work harder when others are watching (thre social facilitation effect), as well as cases when performance on complex tasks is hindered by an audience. She also explains how to bypass the social loafing effect, which is a motivation deficit that often occurs when working with others on group projects. Overall, this was a useful section.

Get it done!

I liked this book. Fishbach packed in a ton of the theory behind motivation, setting goals, battling temptations and procrastination, and getting more done, but with clear explanations that make it accessible. There was practical advice; some technical bits; plenty of information you can use to be motivated and achieve your goals!

I wrote 200 words a day for two years. Here's what I learned.