How to Level Up At Anything: Using Science to Approach Mastery

I stood barefoot on the chill floor of the auditorium, dressed in the thick white fabric of my new gi. As I waited for the other interns to join me, I shifted my weight onto my toes, stretching, and tightened the white belt wrapped around my middle. Soon, a handful of other young college students joined me on the floor. An older man with a gray beard stepped out in front of us. The taekwondo class was about to begin.

It was my third week at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. Most people don't work at NASA to learn martial arts, but my mentor for that summer internship happened to run the taekwondo club on campus, and encouraged all his interns to attend.

We stood in a loose circle as the instructor demonstrated stances, kicks, and blocks. I watched, imitating the movements as I watched (even though everyone else was standing still). When it was our turn to pair up and try out the movements, I moved slowly. I practiced each action carefully, double-checking with my partner that I was placing my feet correctly, walking through the actions several times before speeding up to match everyone else's rate.

Practice makes better, because nobody's perfect.

Competence and mastery

Competence is one of our three core psychological drives (read more about the others). In this sense, our drive for competence is an orientation toward mastery. We want to level up. We are intrinsically motivated to improve at whatever craft or skill we have chosen to pursue. We want to feel that our actions effectively transform our environment.

When we don't have this sense of progression and improvement, we're miserable. Patrick Leoncini, in his book Three Signs of a Miserable Job, wrote that people cannot be satisfied or fulfilled when they are not respected or known in their job, when they feel their work does not matter, and when they have no clear way to gauge progress in their work. (I discussed this idea previously in relation to leveling up in daily life.)

You need to know that you're making progress. And to know it, you first need to make progress.

No matter what you are trying to master, there's a formula you can follow. Whether you want to improve your writing, become a more patient parent, or cook a finer meal, the key to level up skills is twofold: (1) intentional practice and (2) input.

(Read: Why You Should Pursue Excellence, Not Success)

Intentional practice

First, you need to practice the activity. Practice doesn't only mean doing the activity—practice is different from mere doing. You can do an action a thousand times or ten thousand times. If you're doing it wrong and not paying attention to what you're doing—if you're repeating mindlessly—then you aren't practicing.

Practice involves mindfulness of body and behavior. You attend to how you move, what you do, how you craft, what you add or do and when, how the world around you reacts, how you interact.

Doing is following a recipe by rote or filling in a paint-by-numbers. Practicing is what I've done with my sourdough bread: experimenting with how long to knead to get the best crumb, trying variations on the same recipe, seeking to understand how all the parts come together to influence the result. Practice is working on different brush strokes or trying out new techniques of mixing and layering colors.

When I was a fencer, practice often meant slowing down. As my coach would say, practice perfect. Slow down until you can do it right. So I would repeat my parry-ripostes slowly and add speed later. The practice that matters for a tournament today is not whatever high velocity bout you fenced yesterday, it's the slow, careful practice you did six months ago.

"The time for gaining maturity by practice isn't during the playoffs, when things are stressful and demanding. Decision making is stressful, so the best time to prepare for good choosing is when there's no choice at stake." - Designing Your Lifeby Bill Burnett and Dave Evans, p268

Whatever the domain, practice is about trying, attempting, exploring, experimenting, paying attention to what happens, and modifying your behavior based on the results. Practice is mindful action. Practice is incremental improvement.

When choosing what skills to practice, one strategy is to focused practice, i.e., practice the things related to the activity that you're bad at, so that you stop taking shortcuts and working around them. Stretch your abilities.

(Related: How to Build Self-Discipline: Why Awareness and Intrinsic Motivation are Key)

Input

Practicing on your own only gets you so far. You're a closed system. To improve further, you need outside input. There are two strategies: Seek critical feedback from peers and experts. Observe peers and experts at work.

The challenges with feedback are first, how to find people who can provide useful feedback, and second, how to take and apply the feedback you receive. The challenge in learning from observation is learning how to apply what you observe.

How to seek feedback

You can find people to give you feedback in a variety of ways. Perhaps you are trying to improve via a more formal educational setting, such as a community college class, online course, higher education, or classes at a club, gym, or community center. In these cases, there is a built-in instructor or expert who you can approach for advice. You can also approach the other people in the class for peer feedback.

In less formal settings, finding people can be trickier. Look for local groups, clubs, or communities of people who are pursuing the same activities or skills. Some of these groups may be organized online via (such as via Facebook or meetup.com), or at the local library or community centers. Ask your friends and family whether they participate in the same activity or whether they know anyone who does, who you could connect with. You may also be able to find remote communities online.

In short: finding people is a matter of networking.

Getting feedback

Once you've identified people, ask them, politely, whether they would be willing to give you some feedback. If you have a deadline in mind, ask in advance of the deadline—days or weeks, not hours!

Provide guidelines about what you'd like feedback on. For instance, you may be working on more detailed, technical skills, so you're seeking detailed, low-level feedback. Or perhaps you're working on the bigger picture and would like higher level, more general advice on structure and approach. Telling your feedback-giver what level of feedback you're looking for can help them tailor their advice, comments, and reactions, and thus make the experience more worthwhile for everyone.

When seeking peer feedback, try a reciprocal approach. Offer your own feedback in return for theirs. In the writing world, this may look like exchanging draft chapters so you can both comment on each other's work. The practice being critical of someone else and observing with the intention of helping them improve can help you apply the same kind of critical eye and observation to your own actions.

You can learn a lot from peers. Someone else who does the same activity as you—who also isn't an expert—can look at what you do and share their reactions. They don't have to suggest fixes—and in fact, in some cases, like writing, the best person to fix identified problems is the author, not readers (as discussed in my review of Good Prose: The Art of Nonfiction). You can work on fixing identified problems, perhaps using advice from experts.

Sometimes, people you ask for feedback may become more formal mentors or critique and practice partners.

(I've written elsewhere about getting feedback on your writing.)

Taking feedback

Approach feedback with an open, learning mindset. Your goal is to improve. Critical feedback may make you feel uncomfortable or be hard to hear. But if you asked for it—and you did, because you want to improve—you do want to hear it. With luck, the feedback you get will be couched in positive terms. This should hold true especially if you asked someone who cares about your improvement, who shares your goal for yourself and is thus invested in you.

First, listen. Let the feedback sink in without judgment. You sought feedback so you could improve; the entire goal is to use it to get better. You knew, going in, that you weren't a master yet. So don't feel bad when someone else tells you you aren't a master yet. Learning to hear feedback is a skill to practice and cultivate, like any other.

Feedback will vary in length, tone, and helpfulness. Sometimes long, highly critical feedback can come off as negative, but often, it means the person giving you feedback is really trying to help. Sometimes people will try to point out problems and suggest fixes; you don't have to take their suggestions verbatim! Just seeing where someone else thinks improvement is needed—such as in a piece of writing, where they were confused—can be very helpful.

Focus on what you can do better rather than on what you did wrong. Learn, and move on.

(Read about how I've dealt with the long revision process in academic writing.)

Learning from observation

Humans are good at learning from observation.

Seek out experts in your chosen activity and watch what they do. Make notes on what seems to be working for them. Then, try doing that yourself. Model your work on what the experts do. Pick one thing an expert does and imitate it intentionally, as an exercise.

See what the non-expert do, too. Make notes on why what they're doing isn't working as well as it should. Imagine how they might fix it. For instance, when I read science fiction and fantasy novels, some are clearly amazing, and others are … not. I try to identify why particular scenes or characters aren't working.

When I was a fencer, I'd watch other people's fencing bouts. I watched bouts between expert, A-rated fencers—the people I aspired to be. I watched my teammates at practice, and we'd give each other comments and advice—peer feedback. The practice of giving feedback helped me become a better observer, which helped me later, when observing opponents who I'd be fencing next.

For my current endeavors in writing, I seek input on what good writing looks like by reading good books, reading books about how to write well, and listening to podcasts about writing.

Flow and effort in approaching mastery

Approaching mastery through practice and input is not always fun. It doesn't involve constant flow—i.e., a state of sustained engagement, clear objectives, quick feedback, and the optimal level of challenge. Instead, there will be periods of incredible effort with very little to show for it.

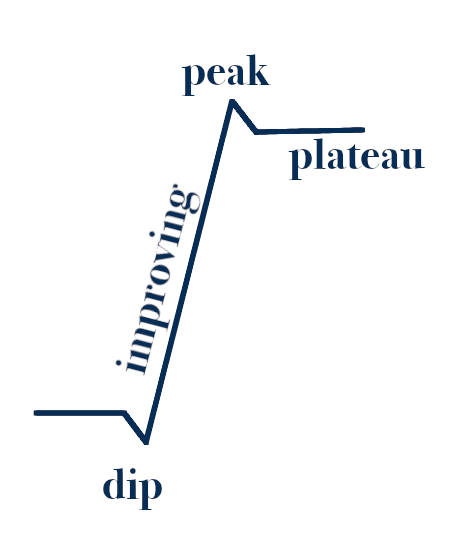

My first fencing coach would draw a line like this on the white board:

This, he would tell us, was a learning curve. You put in effort, and at some point, you start to feel like you're getting worse, but then your effort pays off. You improve. You keep improving. But then you dip again, and it feels like you're stagnant. That's a plateau. Plateaus can last a long time. But if you keep putting in effort, you'll climb up the learning curve again.

Your performance is an equation made of two things: talent and effort. You can't control talent—it's innate, it's your genes, whether you're over 6 feet tall or 5'1", whether you have an affinity for art or not. Talent matters, but you shouldn't worry about it. Effort is the part of the equation you can control. Time and effort put into training and improvement are what matter.

As Ayelet Fishbach wrote in her book Get It Done (read my review), mastery comes from years of intense practice, not from innate talent. The performance of Olympic swimmers was best predicted by the time and effort they put into their training. She said,

"Mastery is an asymptote."

Keep approaching, keep improving, keep striving. Work for what you value. Aim for iterative improvement.

With intentional practice, intentional awareness and examination of the activity or skill, you can get a sense of where you are. And with outside input and critical feedback, you can get a sense of where you can go, and how you can get there.

Credit for this post's header image: koreanet on flickr via Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic (CC BY-SA 2.0)

Book Review: Get It Done: Surprising Lessons from the Science of Motivation by Ayelet Fishbach