Book Review: Arbitrary Lines: How Zoning Broke the American City and How to Fix It by M. Nolan Gray

"[Z]oning is not a good institution gone bad. Its purpose is not to address traditional externalities or coordinate growth with infrastructure, as suggested by zoning defenders and envisioned in the sanitized SimCity version of city planning. On the contrary, zoning is a mechanism of exclusion designed to inflate property values, slow the pace of new development, segregate cities by race and class, and enshrine the detached single-family house as the exclusive urban ideal—always has been. " - Arbitrary Lines, p30

Arbitrary Lines: A book about zoning?

Arbitrary Lines: How Zoning Broke the American City and How to Fix It by M. Nolan Gray explains what zoning is, how zoning laws came to be, why we should care about them, and why, ultimately, we ought to abolish zoning entirely—plus, what we can do to reform these laws in the meantime. It's a practical book at heart. A full third is dedicated to explaining how we could manage land use and growth in a way that respects the complex nature of human cities and the uncertainty inherent in complex systems—a way that, unlike most zoning laws, doesn't assume we have the wisdom and foresight to control everything perfectly in a top-down fashion.

"Even if we could eliminate the bad incentives and special interests that will inevitably distort zoning, the real world is just too complicated for this ideal of planned efficiency." Arbitrary Lines, p142

I was excited to read this book. You might think it's weird for someone to be excited about a book on zoning, which you might suspect to be a dull, dry, dreary topic… but you're reading a review about a book on zoning, so who's weird now? My excitement was not misplaced! Arbitrary Lines is packed with well-researched information. It felt like a fast read; despite the potential dryness of the topic, I never felt like I was slogging.

I've been on a localism, architecture, and urbanism reading binge lately—books such as A Timeless Way Of Building by Christopher Alexander, Transportation for Strong Towns by Chuck Marohn, Wendell Berry's The Unsettling of America... This book fit right into my reading list. I was curious about zoning's history and how it fits into the broader picture of increasing localism and building strong towns. I had the sense it was important … but hadn't realized how important.

What is zoning?

"At a basic level, zoning is how government regulates land uses and densities on private land in most US cities and suburbs." - Arbitrary Lines, p34

As Gray elaborates, use is the things you can do on a property: can you have residential buildings? Can you have commercial or industrial uses, or an unusual uses such as a hospital complex? How intense can that use be—e.g., multifamily apartments, or only detached single-family homes? Most cities today have flat zoning and strict use segregation, which means you can only build what is explicitly permitted in that use district.

Density covers the size and shape of allowed buildings: how big, how many, and what kind of space you have to put around them.

Zoning laws also cover how you can get exceptions to the regulations.

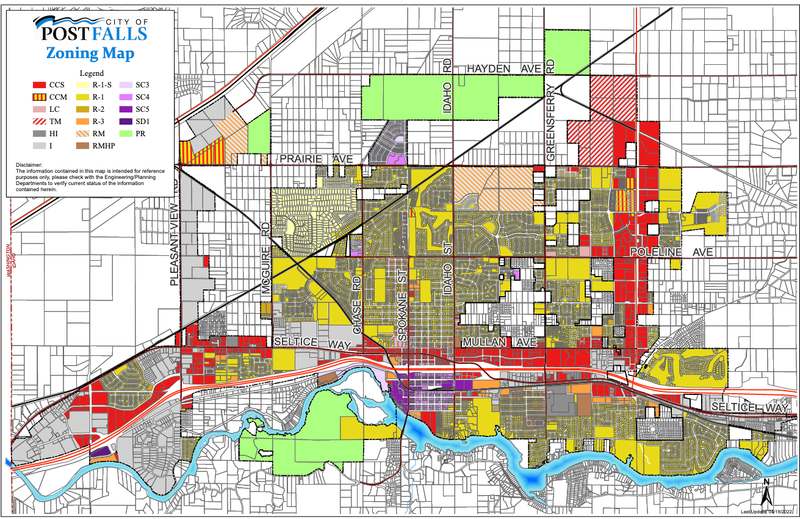

Zoning is how you get the typical city layout, as shown in this fairly typical zoning map:

As Gray writes,

"Generally speaking, the typical city is zoned to restrict offices and storefronts downtown, a mix of commercial and industrial along key corridors, and low-density residential everywhere else."

Most of the zoning map is low density residential neighborhoods, with just a sprinkle of mixed use zoning and just a dash of affordable housing such as apartments—usually in places where they can be used to separate the low density residential from the industrial and commercial.

(Read: Recovering Beauty in Modern Life)

Why should you care about zoning?

Because zoning doesn't work.

"[Z]oning has failed at a basic level to achieve even its stated aims. It has failed as a way to ensure land-use compatibility, ignoring real externalities while focusing on frivolous concerns, and it has failed as a way to manage growth, frequently working in opposition to broader city planning goals and strategies." - Arbitrary Lines, p142

Why does zoning fail? In part, because it's an abstraction: broad, abstract rules that are supposed to apply everywhere equally in a city, without considering the complex cases of the real world. Zoning tries to head off conflicts before they arise, but conflicts arise anyway!

Gray gives the example of a beer garden. Beer gardens can be loud. The noise could affect neighbors. This is a negative externality, a cost imposed on neighbors. However, other neighbors might like having a beer garden within walking distance of their house. They consider their proximity to be an amenity. Same with corner grocery stores in residential neighborhoods: being able to walk to a corner grocery might be very nice for some people; others might consider it unwanted noise and traffic.

One neighbor's amenity is another"s negative externality. Who's right? What should be enshrined in zoning law?

As is, most zoning codes solve this dilemma by moving less desirable uses of land and uses that have, perhaps, more negative externalities than positive to be located near the less affluent areas of the city. Look at any zoning map: Gray points out that single family residential is nearly always "buffered" from any kind of industrial or commercial district by all of the multifamily residential districts. The affluent homeowners are protected; the more dense and less affluent residents suffer any possible quality of life decreases.

Is that how you want to treat the poorer residents of your city?

Growth means change

Another problem with zoning is that it prevents change. Cities ought to grow, change, and adapt to fit their current population.

It doesn't make sense to write in law that a city or part of a city is not allowed to change.

Gray asks,

"Take the appeal to "community character," a mainstay of zoning justifications. At best, this argument casts all change as imposing a kind of cost on neighbors, to the extent that it upsets some nebulous aesthetic quality of the neighborhood. In practice, this often means upholding yesteryear's ideal of a squad house on a vast lawn in the suburbs and arbitrarily capping building heights in cities, regardless of how much broader demographic and economic conditions have changed.

At worst, the "community character" appeal often serves as a dog whistle for preserving the existing racial and class makeup of a given place, particularly concerning zoning approvals that might allow less affluent residents to move into a neighborhood." - Arbitrary Lines, p139

This part resonated. The "preserve character!" argument has been all over proposed local developments lately—anything that might indicate a shift toward density and away from large single-family lots.

Gray also acknowledges a common concern is that growth is bad in cities, not all growth is good, aren't cities bad for the environment? He presents data showing that the opposite is true: people living in dense cities have a lower carbon footprint than their suburban counterparts.

How did we get zoning?

Another reason zoning fails is because it is segregationist. Gray spends the first couple chapters relating the history of zoning and the impact it has had. He explains the segregationist roots—some early ordinances were very explicit about it, including one adopted in Baltimore in 1910 that "restricted African Americans from buying homes on majority white blocks, and vice versa". And while the courts eventually decided racial zoning was illegal, zoning codes often fell back on economic segregation, which had racial implications. Gray presents compelling data on the role zoning has played in segregation within cities.

"Zoning reserves the best parts of every town for an elite few—not only the best housing, but also often the best school districts, the best public services, and the best access to jobs. If it shows up in the data, with basic quality of life metrics like life expectancy, lifetime earnings, and educational attainment varying dramatically from neighborhood to neighborhood and suburb to suburb" - Arbitrary Lines, p89

Gray explains how at first, it was municipalities adopting some form of zoning, but by 1936, there was an enormous push by the federal government for everyone to adopt zoning, led by Herbert Hoover and his advisory committee on City Planning and Zoning. The committee developed model legislation that everyone could adopt, which is how we all ended up with such similar zoning codes.

The justifications for zoning were noble enough—preserving health, safety, reducing congestion—but there was no data showing that zoning would actually accomplish those goals.

How does zoning affect housing prices?

First, zoning regulations are linked to higher housing costs. While this may be great for boomers who are using housing as an investment and want property values to stay high, it's not so great for younger families who want to own their own homes.

"Between 1970 and 2010, median home values appreciated at a rate of nearly three times median household incomes, particularly in prospering coastal cities." - Arbitrary Lines, p52

Zoning increases housing costs by blocking building of new housing, especially affordable or more dense housing; it also may require housing to be built of higher quality, with larger buildings or larger minimum lot sizes than people might otherwise desire or require; and also raises the cost of building new housing because of it adds red tape through review and permitting. In zoning regulations, there are frequently explicit bans on building apartments or on subdividing buildings. Even when allowed, height limits, minimum setbacks, and maximum floor area ratios frequently make it difficult to build any kind of dense housing, leading to the missing middle.

Gray tells us about a study finding that 40% of Manhattan would be illegal to build now under today's zoning.

The wealth denied us

There's an interesting chapter arguing that zoning has alao interfered with the creation of wealth, and is part of the reason why America is declining. Gray explains how cities are centers of wealth and innovation: people move to places with higher median wages, from poorer areas to wealthier areas, and cities are wealthier areas in large part because of the increased size of the labor market. More people, more competition, more specialization. More mixing of ideas, more innovation.

But there's a weird thing happening now: people are moving away from cities. That's backwards! They're moving from wealthy areas to poor areas, because they've been priced out. They're paying a third to half their income in rent. In large part, that's because of zoning: housing isn't allowed to be built densely and a housing crisis ensues.

This is a major issue, argues Gray, because of the implications for our economy, for innovation, for the things that made America greater than other nations. He argues that we're losing that, in part because of policies that try to make housing an investment, lock in property values, and instead make housing unaffordable.

But I've heard zoning is a good thing!

There are people who argue the other side of the zoning story—here is one—but I think they miss a lot and Gray tackles all their objections in ways I found persuasive.

They tend to look at zoning only through the lens of money. They assume that high property values are a worthwhile goal. They ignore the impact sprawl has on the environment and on communities; they ignore concerns about atomization in suburbia. They often think the answer is not to build more densely, but to increase sprawl … without considering sprawl at what cost?

They fall into the all-too-common trap of assuming that if we could only manage and control and plan better, then we will surely build great cities and towns. They argue that zoning makes areas nicer by keeping out inappropriate uses, but as Gray argued, zoning is bad at that. One person's nuisance is another person's amenity. Zoning is an abstraction that can't apply neatly to the messy real world. Human cities are complex systems that cannot be controlled or planned top-down; the way to improve them is with little bets and incremental changes.

Plus, abolishing zoning does not mean abandoning all kinds of city planning or land use and growth management. It just means abolishing zoning, so we can move on to more effective ways of dealing with the complexity of growing human cities.

No zoning? No problem.

Gray dedicates a chapter to Houston—the legendary American city that never adopted zoning in the first place. No zoning! And it's not all sprawl! How did Houston manage to grow into the fourth-largest city in America without careful rules about land use and development? Gray writes,

"The issue of land planning can be reduced to one question: How do we determine what should go where? While zoning tries to solve this problem through brute force, thinking through every conceivable land use and where it should go, a more elegant solution reveals itself in Houston: for the most part, the uses sort themselves out." - Arbitrary Lines, p152

There are many factors that nudge people to build and develop and live in different parts of a city, whether it's a need for cheap land, access to transportation or railroads, concern for whether streets are quiet or not, and so on.

Plus, Houston has other laws and rules that solve the problems zoning attempts—and fails—to solve. For instance, deed restrictions. Deed restrictions allow certain communities to opt out of non-zoning and have their own land use rules in their certain areas. They are private voluntary agreements among property owners, a bit like an HOA; they have term limits (so they have to be reapproved after some number of years); they're often tied to the real estate market. For instance, if the rules are too strict for buyers, sellers may have to lower home prices. This may encourage people to think about the implications of stricter rules for home values and future use in the area before adopting those rules.

Houston also has specific rules about troublesome or nuances, such as the slaughterhouses remaining 3,000 feet from nearby residences, rules about development on the floodplain, and plenty of other rules, too. Some are opt-in. But because the zoning-like rules from deed restrictions only apply to certain collections of properties in certain neighborhoods, many places that are ripe for redevelopment or infill are available for exactly that—such as vacant lots, parking lots, and many areas downtown.

What's after zoning?

Gray uses Houston as a kicking off point into the future of unzoned cities. Gray discusses the roles of different levels of government in reforming and abolishing zoning; he makes the case that there are things we can do locally to improve the situation!

Here are the low-hanging fruit of zoning reform, which Gray explains in detail:

- End single-family zoning—allow incremental dense growth, such as allowing citywide duplexes or triplexes, or adopt a liberal accessory dwelling unit (ADU) ordinance

- Abolish minimum parking requirements—developers can determine the right amount of parking for a project themselves

- Eliminate or lower minimum floor area and minimum lot size requirements—don't make people buy what they may not want

- Allow affordable housing typologies—don't outright ban dense forms of housing such as apartment buildings or single-room occupancies

- Remove barriers to building, such as streamlining permitting and inspection processes

Later, once zoning is abolished entirely, Gray recommends ways to make everyone happy: regulating actual nuisances, allowing opt-in deed restrictions like Houston does, providing mediation for neighbors (there's a great example in the book of a bar located in a residential area, where talking to their neighbors helped resolve conflict), community land trusts, and more.

The future of cities

If you're interested in the future of cities—especially if you're also into localism, subsidiarity as applied to urban development, or developing robust communities—then this book is for you. If you've ever been curious enough to find or read part of your town's zoning code before picking up this book, then Gray will give you the insight and background you need to understand why the code is the way it is.

After all that, I have lingering questions … not questions unanswered by the book, but questions prompted by it, about the state of local planning and how we might implement some of Gray's recommendations. Not a bad outcome!

Productivity and Balance as a Parent: Challenges, Ideals, and Strategies