How Can We Fix the Academic System For Women?

While I was in full-time academia as a grad student, September meant the switch from summer work (research studies, writing papers, writing code for robots) to semester work—more research studies, more writing papers, more code, and also classes, group projects, paper reading groups, meetings, and other campus clubs and events.

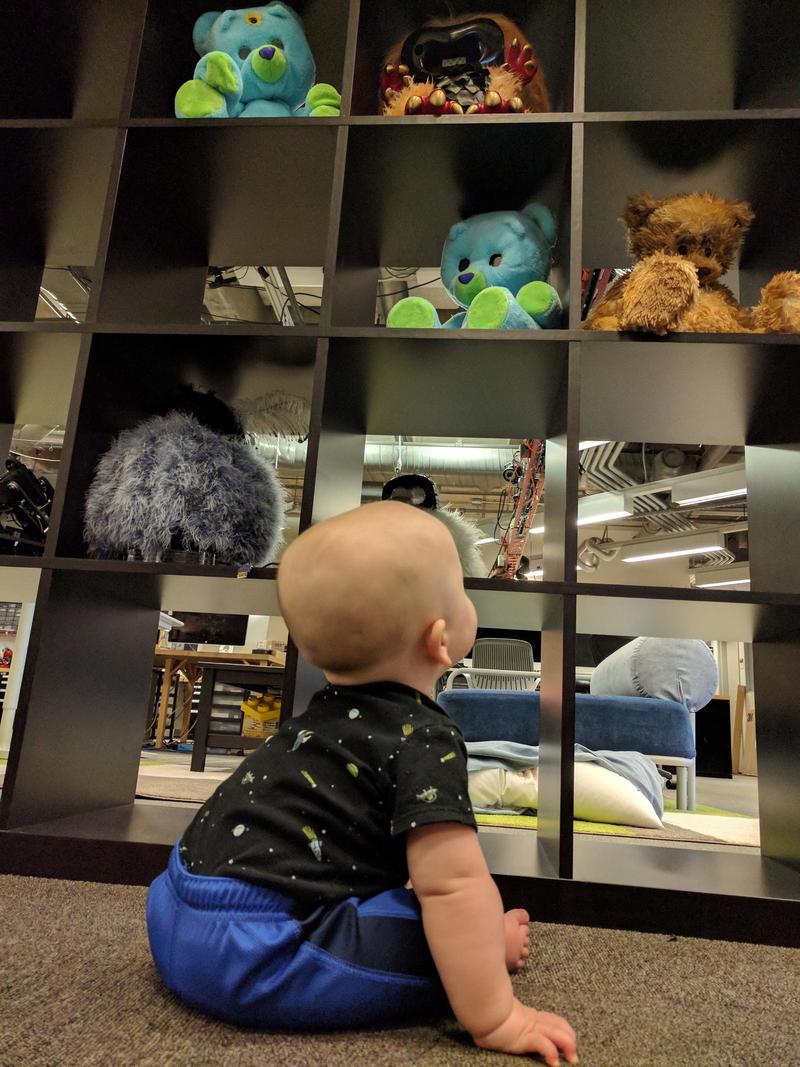

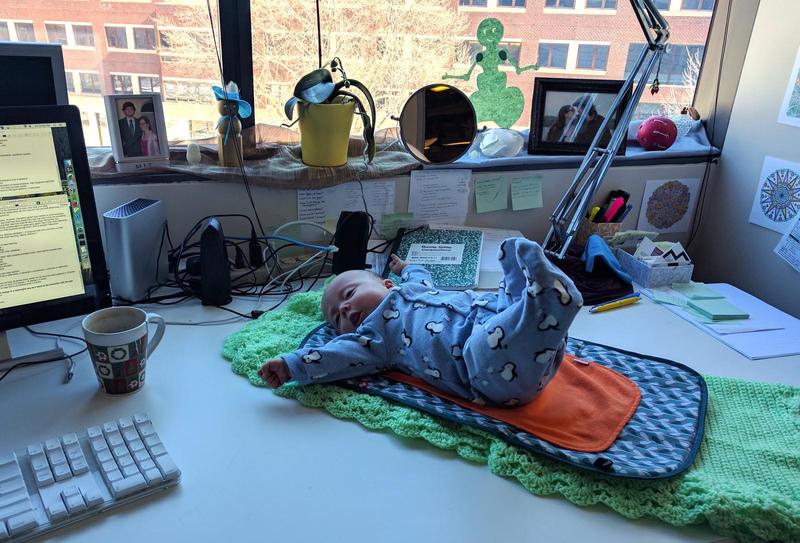

In my fourth year at MIT, September also marked the transition from second trimester to third, and a ramping up of preparation for the biggest change in my life. I had my first child in grad school. Although I did get a couple questions like, "Why aren't you waiting until you have tenure?", parents make up at least 10% of the grad student population.

(Read more about my journey having children in grad school, and beyond)

With the start of the academic year, I've been reflecting on work I do now and how my life in September is radically different than it used to be—even three years ago! I'm also thinking about balance in academic life, because my book Grad School Life: Surviving and Thriving Beyond Coursework and Research came out a few months ago.

Systemic Problems: Academia is Failing Women

Academia has an ingrained, usually implicit assumption that either you have no family (like the monks who built the ivory towers of yore) or your family comes second (which has been fine for most men, since women traditionally did the child-bearing and child-rearing). These assumptions often place women in a difficult position—especially women with families.

For example, there's the "baby penalty": Men with kids are 35% more likely to get tenure than women with kids. Having kids changes or ends women's careers more often than men's. Women are outnumbered at high academic ranks, despite their often higher levels of productivity. Part of that is due to the leaky pipeline: Although women make up more than half of the graduate student population, they're also twice as likely to leave academia after having kids—around 43% of women leave, compared to only 19% of men. Only 44% of tenured women have kids, while 70% of tenured men do.

All these statistics are well-known. They're increasingly discussed alongside calls to action, one of the most common being a call for better parental support policies, such as paid family leave. But these statistics also reflect a truth about reality: that "having it all" is a myth.

What usually falls off the radar is opportunity cost. You can "have it all" only at the expense of something. (And no, we can't just sacrifice sleep.) Time is finite. It is literally true that doing some things means not doing other things. Taking weeks, months, or years to give birth, care for an infant and/or small children, and recover physically and mentally can put women behind on the career ladder. Time spent with family is not time spent chasing grant money. On the flip side, long days in the lab and the library, long nights drafting papers before deadlines, and traveling for conferences and talks will all cut into time with your family. Academics often work 60+ hour weeks (though there is some debate and efforts to quantitatively verify that number).

The more women try to have it all, the more we fall behind. And that's because of the system.

(Read: How Women Scholars Manage Stress, Goals, and Self-Care—And How You Can, Too!)

Why should we fix the academic system?

The statistics I cited above show that the current academic system isn't working for a lot of women. It didn't work for me. It's time to change the system to better suit women, rather than assuming that women can and should mold themselves into the existing structures.

We should want to fix the system because diversity in academia is valuable. Women will ask different questions than men. They will pursue different research interests and interrogate research questions in different ways. Diversity leads to innovation. There's plenty of research on this, and also common sense: on average, women and men are interested in different things. People who are interested in different things will study different things.

Second, many women want one or more kids. Like me! When I started grad school, I didn't know for certain that I'd have kids during school, but I was sure I wanted them. Academia will not be fixed by assuming that women will choose to forgo or postpone families. There's a biological reality to when you can have kids and the fact that most people desire them (Surprise: Children are desirable! They're fun! They're the future of the human race!) Grad students are, on average, 33 years old, and women's fertility peaks before that. I know many academic women who have struggled with infertility. I also know women who have had several children into their 40's.

Third, women with careers who want to have kids will have kids sometime during their careers. There's no other time to have them. Some people, like the ones questioning my decision to have kids while still a student, probably think waiting is less stressful. I doubt being an early career researcher is less stressful than being a grad student. There's no ideal time to go on maternity leave. Or, glass half full: there's no bad time! Solutions I'm looking for will enable women to raise their children while continuing to build their research careers, if that's what they want to do.

(Read: Productivity and Balance as a Parent: Challenges, Ideals, and Strategies)

What kinds of systemic solutions do we need?

Women face different challenges in parenthood than men. Being a new mother who just gave birth is very different from being a new father who didn't (just ask a new mother). The physical recovery alone is tremendous. There's a reason why men use their extra time during parental leave to write more papers and get ahead, while women mostly just… recover. Sleep, eat, rest, feed the baby, snuggle the baby. These differences need to be taken into account in any potential solutions.

I've seen many calls for improved parental leave policies. While that would be great, a lot of mothers would rather have the option for part-time, remote, or other more flexible work arrangements than just the straightforward full-time-off then full-time-back. The wage gaps are mostly driven by a quest for flexibility rather than sexism. The changes we need should not try to make women's lives more like men's lives, such as attempting to hide all evidence of baby-making away in three-months paid leave, because most women don't want that. Rather, we need to adapt the entire system to better align with the kind of lives women want to lead.

At the core, the issue isn't about women working while having kids. It's a broader issue: a devaluing of motherhood. A devaluing of the work of caring for and raising children (mentioned here), a devaluing of the contributions mothers make to society, whether in the home or out of it. Staying home is associated with a lack of status. Any changes to the academic system must acknowledge all this. I have a lot to say on this topic that you'll be seeing in future posts. Below, my ideas are actionable, but without a change to culture at large regarding how motherhood is perceived, these measures can only go so far.

(Read: What Does It Mean To Be A Scholar?)

Change Research Culture

One place to start is with the workaholic research culture. For example, Lisa Barrett recently wrote about the problems with the publication arms race—the idea that to succeed in academia (specifically for her, in psychology), you need to churn out 5-10+ papers a year, each containing reports of multiple experimental studies, all entailing enormous amounts of work and funding. She suggested some ways to start changing the culture:

"Each of us, the next time we’re on a search or tenure-and-promotion committee, can commit to reading applicants papers instead of counting them. Each of us, when sitting down to write the next manuscript, or even better, to design the next set of experiments, can ask: Will this research contribute something of substance?"

Quality work doesn't have to be done (and perhaps shouldn't, and can't, be done) really fast to be quality. Changing our expectations from quantity to quality would mean that scholars who opt to work fewer hours (say, 40 hours a week instead of 60, or part-time instead of full-time), and as such produce fewer publications, would still be seen to be contributing meaningfully to their fields. Women can be committed to their scholarly work while also being committed to their families.

We need to normalize and promote motherhood in academia. For example, Sarah A. Birken and Jessica L. Borelli suggested in the Chronicle in 2015 that women ought to stop doing "women's work" (such as teaching and service) unless it's what they love to do; stop promoting workaholism and instead lift up balance; and stop hiding the realities of motherhood, such as pumping milk or picking up the kids. Normalize taking time off for family. While most institutions let women stop the tenure clock and take a reduced teaching load when having a baby, some women feel like they can't take advantage of such policies right now. We could also add provisions to grants and fellowships that allow the use of some funds for childcare or other household help, so that women could spend less time on chores and more quality time with their kids and on their work.

(Read: Is Going to Graduate School Worth It?)

Create Part-Time Opportunities

Given the desire of many parents for flexibility, let's create more part-time research opportunities. A few part-time positions exist now (including a cool dual-career couple who share one full-time faculty position), with generally positive results.

Funding agencies should create more grants that pay out less money over longer timelines for part-time research. We could set up shared lab spaces or shared offices for part-time faculty. Build co-working spaces that include childcare (here's one). Reduce or remove teaching loads for part-time research faculty. Pay the part-time faculty a little less each, and use the money to hire an extra admin or lab manager to help them out, freeing up their time for actual research work.

(Read: How Do You Decide What Projects to Work On As a Scholar?)

Support Independent Scholars

Not everyone wants or will get a job at an academic institution. What if it were easier to be an independent scholar? This may also fit in with the part-time and flexible work option.

That's the issue a few organizations, such as IGDORE, are tackling. They enable independent scholars to join forces, so to speak: creating new academic networks, helping administer grants (since many funding agencies require an institutional affiliation), helping independent scholars find funding in the first place, and more. They're even forming independent IRB systems for human subjects study approval. One problem they haven't solved yet is library access, though the push toward open access publishing may help. The scholars in these organizations are at the forefront of reimagining what the academic world could look like.

Mothers Make Valuable Contributions

These changes would be a start, though there's plenty more to change to get us to a place where children are celebrated as boons to one's creativity and motivation, rather than treated as obstacles to advancing one's career. As Patricia Maurice wrote, having kids makes you a better faculty member and a better person, and being faculty can make you a better parent.

Women can be highly productive researchers and amazing mothers simultaneously. Let's fix the academic system to make it easier for them to be both.

Like this post? You'll find even more detailed advice about managing grad school and life in my new book, Grad School Life: Surviving and Thriving Beyond Coursework and Research. Order it today!

Project: Tapestry Weaving on My Lap Loom