Learning to Identify Local Wildflowers

"Wait up! I just have to see if this is a new flower!"

I peered down at a yellow-petaled beauty. The leaves were shaped differently than similar flowers I had spotted, elongated and a slightly darker, more foresty green. The arrangement of petals seemed different, too. I pulled out my phone to capture a few pictures. As much as I wanted to identify it right away, it would have to wait—I was hiking with my kids and a couple other homeschooled families in a local nature preserve, and hiking worked better if I didn't stop to admire the flowers every five feet.

That yellow flower was one of over a hundred that I found and identified last year. I began taking photos of local wildflowers in March, when the first buttercups poked their yellow faces out into the sun. Every week, at whichever nature park my forest school group was at, I searched for more blooms. (Relad more about our group.)Our group rotates through various parks in our area, so I got to see the flowers popping up in the varying ecosystems—the rocky hills, the sunny meadows, the wet and cool cedar forests. When we returned to a park weeks later, I could see new flowers blooming, earlier blooms going to seed, and other buds holding out for warmer weather.

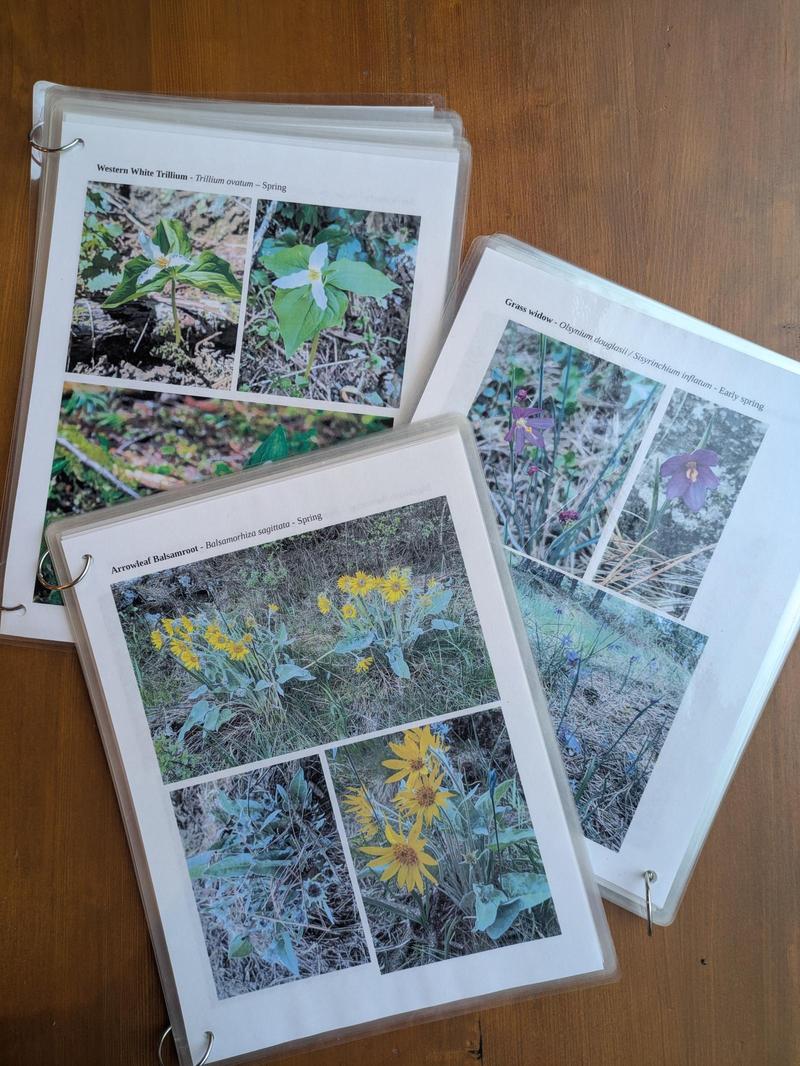

By the end of May, I had identified over eighty flowers. I had also misidentified one, but I fixed it later. By the end of the summer, I had over a hundred in a homemade laminated flower guide book, loosely organized by color (yellows and oranges, whites, blues and purples).

(Read: Book Review: Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer)

Why bother learning about wildflowers?

My purpose for learning flowers was threefold. First, I wondered what they were! I wanted to know the names of flowers that grew near me, just to know. As Zena Hitz wrote in her book Lost in Thought, not all knowledge need be pursued for some useful end (read my review). Knowledge doesn't have to be instrumental.

Second, I want to learn more edible and medicinal plants. Becoming more familiar with local plants generally will make it easier to learn which ones are beneficial or even delicious if I taste them. It's trickier if I have to both learn to identify the plant and learn what it does at the same time.

Now that I'm more familiar with the flowers here, this year, I might branch out into how to use them. Or perhaps I'll start learning shrubs, trees, bugs, or birds!

Third, I want my kids to learn about local plants. I want them to learn about edible and medicinal plants, and also, I want the local plants to be familiar. Like a friends. Like home. Knowing the plants in our area will give them a stronger connection, stronger place attachment, like Melody Warnick described in her book This Is Where You Belong: The Art and Science of Loving the Place You Live.

(Read: A Poem For Identifying Ten North Idaho Conifers)

What are the benefits of learning local wildflowers?

When I see flowers whose names I know, I feel more connected to the area. A hike with pretty flowers becomes an opportunity for a treasure hunt, like on our trip to Glacier last summer. Many of the same flowers grow near us and in the park.

Exploring the national park was even more fun when I could spot flowers I knew and share them with my family. Since we were at higher elevations in a cooler part of the mountains, the flowers we saw were weeks or even a month behind the ones blooming at home---which meant I had had a chance to identify many of them at home prior to the trip! Some were in my homemade guidebook; others I recognized because they were lookalikes with flowers at home, or because they appeared in one of the wildflower books I had consulted in my identification quest (two of the books were specifically for flowers in Glacier and nearby parks).

I also paid more attention to the ecosystems we passed through. I noticed which flowers often grew near each other, and which I saw in different parks. Certain flowers liked the wet, shady, cedar forests. Others I tended to find in sunny, dry places, in rockier areas, or in meadows. Some flowers liked the woods; others the open skies.

Being aware of these ecosystems at home meant I noticed them when we visited Glacier, climbing through Aspen forests, up higher to places dominated by subalpine first, and even farther up, where the rocky terrain was spotted with shorter shrubs, stonecrops, buttercups, and yarrow.

(Read: Why Outdoor Time is Important for Kids)

What's the process for flower identification?

First, when I find a new flower, I consult my existing wildflower guide to see whether I already captured photos but forgot the flower. That has happened.

Then, I take a few pictures with my phone. I try to get photos of the flower head-on, of the leaves and stem, and the plant as a whole. I use some of the photos for my printed guidebook, and some just for the identification process. Depending on the context, I don't necessarily try to identify the flower right away. Sometimes I'm busy with the kids, or we're hiking, so I need to do some or all of the identification research later!

I generally use a couple apps for my first pass: PlantID, PictureThis, iNaturalist. I don't have the paid version of any. The apps don't always identify the plant correctly, so further research is needed. They can usually get me in the right ballpark, however. Sometimes they identify the genus but not the species correctly, or I can look up lookalikes for the suggested flowers.

I also check in a couple wildflower books for similar-looking flowers. Unfortunately, there isn't a guide specific to the Idaho panhandle. You can find books for the Pacific Northwest, which cover some (but also lots in Oregon and Washington that aren't here), or the Rocky Mountains (same problem). I had decent luck with a guide of wildflowers in Glacier National Park, since it's Western ecosystems are similar to many of ours, and a northern rocky mountains guide. But even those guides don't cover all the flowers found in those places - they just pick a few of the most common species.

After getting a potential genus or species, it's time to search online. There are a ton of useful websites with details about species and where they're found, what differentiates different species within a genus, and so on. For some flowers, a quick search is enough to confirm the species. For others, I've spent over an hour trying to figure out which species among twenty is the one I've found - for instance, with this buttercup.

I don't bother with specific varieties within a species. It's too specific for my purposes, and not really necessary. The varieties also often hinge on technical differences I don't yet understand, or that require a magnifying glass to notice. Getting the genus and species is good enough for me!

Book Review: The Battle of the Classics by Eric Adler