One Year Later, Are Backyard Chickens Worth It?

One year ago, we brought home two boxes of little peeping fuzzballs. They lived in a cardboard box in our garage for several months as they feathered out. Eventually, outside was warm enough and the pullets were big enough to move into their new home: the red coop in our backyard.

By midsummer, our hens were paying rent in beautiful, brown eggs.

(Read about why we got chickens and how we set up our yard.)

How do we like having backyard chickens?

We're enjoying the hens—and not only because store eggs keep creeping up in price! Our kids adore the hens. They often hang out in the run, picking up hens, hugging hens, feeding them weeds and scraps.

Most days, the kids are on egg duty. We have a designated egg basket they use for collection. Our six-year-old likes to count how many eggs there are, and will announce triumphantly, "We got 12 eggs today!"

(Read: Why Outdoor Time is Important for Kids)

We like that we can feed the hens table scraps. Anything the hens don't eat becomes part of our compost pile (more on that in a minute). It's nice to know nothing is going to waste!

They haven't been as much work as I feared. Since we're in the yard almost every day anyway, it's easy to check in on them. We only need to clean out the coop approximately once a month. We stir their pine shavings every week or so, and the tool for that is hung on the side of the coop so it's a quick job. Food and water are in 5 gallon buckets, so we only have to refill them once a week or so (depending on how many scraps they get, and they drink more when it's hot).

The most unanticipated work came when the water heater broke at the tail end of winter, so we had to take buckets of water out twice a day. But even then, we had to go out anyway to toss scraps or fetch eggs.

How many eggs do we get?

When all the hens were laying last summer, we averaged a dozen a day. As the weather cooled, this dropped off. December was especially cold this year. The hens slowed down to around 6 eggs a day.

Then, Randy added a light to the coop, since he had read that extra light would remind the hens' biological clocks to keep at it. Egg production picked back up. Now, we're back around a dozen eggs a day.

We eat about half the eggs we get and sell several dozen a week to friends. If we sold every egg we got, we might be able to pay for all the chicken feed, pine shavings for in the coop, and other chicken supplies with just the egg money! It would take awhile to recoup the initial investments (e.g., in the coop and the materials for the run), though eventually, we might.

(Seasonality and natural rhythms: Why growing and preserving your own food matters)

Winter adventures: How did we add new hens to the flock?

In December, we lost a chicken to a hawk attack. The hawk didn't quite get her—we found her frozen under the coop, clearly dead from the attack, probably having run under in an attempt to escape. We were surprised a hawk had ventured into the yard—the run is mostly enclosed by trees and it's not an easy spot for a diving hawk. But, it was the coldest part of winter. The hawk was probably desperate.

Fortunately, a couple weeks later, a friend who hatches and raises her own hens announced she was downsizing her chicken operation. I bought three Buff Orpingtons, all about a year old, to replace our poor lost hen. They came home in a pair of cardboard diaper boxes.

Introducing new hens into the flock was complicated. We read up on the horror stories—like hens pecking newbies to death.

We don't have space in our yard to set up a separate, adjacent chicken space. So we divided the existing run using some garden netting, set out a bucket of food and a bucket of water, and hoped it would be sufficient. It was January. It was cold. Every night for a week, we scooped up all three new hens and stuck them in a big cardboard box full of pine shavings to sleep. We carried the box into the garage, where it was warmer. We carried it back out and tossed the hens in their section of the run in the morning.

Our divider was non-optimal. Within a couple days, chickens were on the wrong sides of the divider. One of the new Orpingtons kept flying over the fence to explore our yard. But the hens weren't pecking each other anymore than usual, so we let them be. Eventually, we took the divider out. Two of the new hens ventured into the coop at night. The other one flew onto the roof. It kept flying onto the roof for over a week, after which I guess it figured out where the door was.

Full integration took about a week. The new hens still acted shy around us compared to the others—perhaps they were not so used to three-year-olds scooping up hens for hugs.

(Read: How I planted my suburban yard garden, how it grew, and what I learned in Year 4 of gardening)

How we dealt with escaping hens

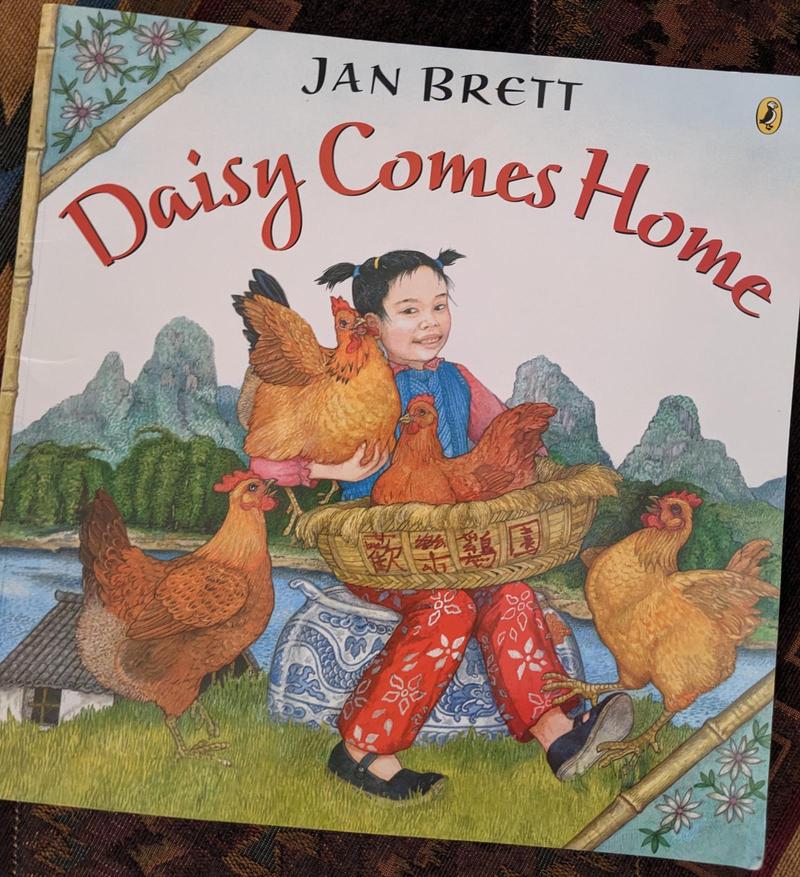

One of our black stars loved escaping the run. She flew over the gate. She flew into the crabapple tree and wandered off along the chain-link fence. Our kids dubbed her Daisy, named after the hen in a Jan Brett book who goes adventuring.

We added more chicken wire along the run to make the fence twice as tall, which helped, but Daisy kept sneaking out anyway. We found a cache of nearly two dozen eggs under our lilac bushes, months after they were laid.

Daisy was joined by one of our new Orpingtons in laying eggs under a bush in the front yard. We discovered they could escape the run via a hole under the chicken wire in the very back corner of the run. We filled the dirt back in. They flew out over the gate and onto the roof of the coop. When they tried to dig in my newly sprouted lilies, it was the last straw.

We stretched bird netting along the edges of the run, over the gate, and above the coop. We added some chicken wire to block the exit via the tree and fence. So far, no escapees. Hopefully it stays that way.

Composting with Chickens

We decided to try composting in the corner of the chicken run. When we toss them scraps, anything they don't eat becomes part of the compost. When we clear out the coop, all that gets added to the pile. We toss in leaves and weeds from around the yard.

For the better part of the past year, I mostly ignored the compost pile. This week, now that the ground is less frozen, I finally stirred the pile to see if anything useful had been happening under all the leaves and chicken droppings.

Not much happened. It looks mostly like wet year-old leaves and pine shavings. There is a bit at the bottom that might be more compost than it was before.

This year, the plan is to stir the pile periodically and read up on how to compost well with chickens. Maybe I need a different ratio of food scraps to chicken waste and yard waste. Maybe there wasn't a critical mass of compostable stuff before winter froze the ground.

On the bright side, there's always more to learn and improve!

Schools Zap Kids' Motivation and Mental Health