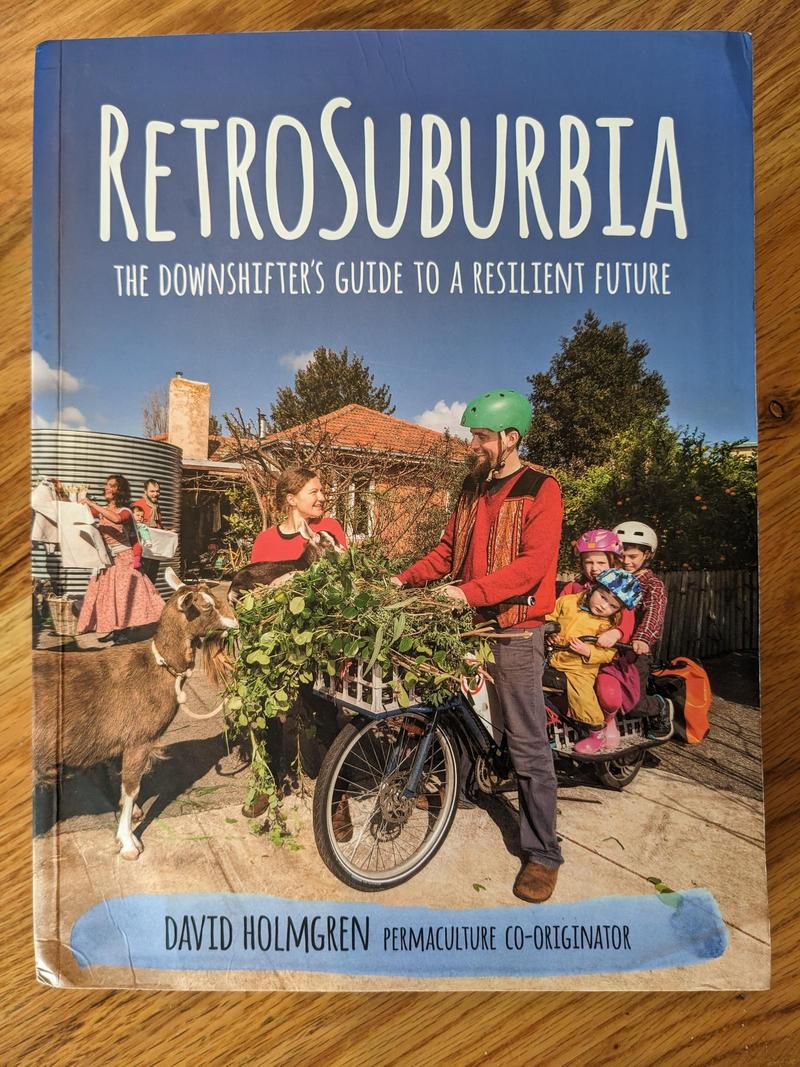

Book Review: Retrosuburbia: The Downshifters Guide to a Resilient Future by David Holmgren

You don't need acreage to live sustainably and productively.

That's the key message of Retrosuburbia: The Downshifters Guide to a Resilient Future by David Holmgren. He wants to help suburbanites become more self-reliant and resilient.

Why it matters: Holmgren argues that we may soon be in an "energy descent" future, that is, a future in which current forms of energy are no longer cheap and convenient, likely fueled by the collapse of the financial and property bubble, rising costs and decreased availability of current energy sources, and increased chaotic weather from climate change. Regardless of your personal views about the likelihood of an energy descent future, it is clear that the future holds many uncertainties—and thus, being more resilient will benefit us all.

Where I live in Idaho, people have a common dream: 10+ acres outside town. Everyone wants to build their own house, try off-grid living, get their own mountain or river view, do some homesteading. But with property values skyrocketing, inflation, and increased costs of living, the 10-acre dream will stay a dream.

Fortunately, Holmgren argues that we can all live more productively and sustainably without the 10 acres. We can retrofit suburbia.

(Read: How We Are Intentionally Building Strong Community Ties)

Dig deeper: Why Retrosuburbia is worth your time

Retrosuburbia is an inspiring book for suburban homesteaders. Holmgren, who is a permaculture co-originator and advocate, presents a ton of useful information, accompanied by illustrations, photos, and case studies (and more online). The book is divided into three sections:

- the built field—properties, climate, heating, electricity, water, storage, etc

- the biological field—gardens, soil, food systems, animals, etc

- the behavioral field—living arrangements, habits, transportation, work and livelihoods, financial planning, health, children, aging, disaster planning, etc

The book is broad, and deep. It's a big book—nearly 600 pages! By necessity, it covers a lot of topics. Holmgren writes,

"[O]ne of the key insights of permaculture that I hope shines through this book is that to survive and thrive in retrosuburbia we will all need to become a generalists to a greater degree." —David Holmgren, Retrosuburbia, p12

Holmgren is big on off-grid living. A big part of downshifting into the energy descent future is figuring out how to live well in a suburban environment while still meeting energy needs—such as retrofitting a house to have better passive solar heating and cooling, solar panels, and compost toilets. Anything that reduces dependence on the grid is promoted.

I was most interested in the later chapters on managing green stuff, community, and personal habits, since those are appealing regardless of what happens with energy.

I liked the emphasis on retrofitting. We're not building on a blank slate; we're already in a context. We already have suburban homes. How do we adapt?

"The focus on retrofitting requires us by definition to accept that we are not designing a system from scratch. Our sites, houses and even households have their own patterns, shaped by their history, which we have to work with, identifying opportunities for creative adaptation without demolishing the structure or the place of our lives.

… whatever we do, wherever we go, there's always a history in an existing situation that we must recognize and accommodate in our plans." —David Holmgren, Retrosuburbia, p30

The Vision: A Green, Vibrant Suburbia

One of the book's strong points is that it demonstrates how green and lively suburbia could be, if only we changed land use, planting, and development patterns. Suburbia doesn't have to be a desert.

Many of the changes are simple. E.g., if people planted fruit and nut trees or berry bushes instead of ornamental trees and shrubs, then they could get local food on their block. Or if people paid attention to the sun when building and orienting houses, we could have south-facing gardens, windows that get morning light, patterns that align with Christopher Alexander's pattern language, which tells us how to make built environments into the kinds of places that people find beautiful and useful.

Downsides of Retrosuburbia

I was hoping there would be more suggestions for adapting suburbia to be useful, not only suggestions for adapting suburbia to be off-grid. I'm not sure what I was expecting—urbanism? Hacks? Upzoning changes? Mixing commercial uses into suburbia, instead of only mixing rural uses? What else can be done with the smaller lots in newer neighborhoods, where people often have barely a tenth of an acre?

Suburbs aren't great for lots of reasons. In a less doom and gloom scenario—what if we don't end up in an energy descent future soon?—what else can we do to transform suburbs into places people enjoy living? Holmgren's vision is one potential transformation: garden farms, embedded communities working together to raise food and sustain each other. But what else can we do, especially in areas like North Idaho that are more closely linked to rural farms that could take on a greater share of food production?

I know Holmgren was deliberately focusing on what individuals and households can do to be more resilient—he was intentionally not discussing the community or government levels—but I still wanted to know what else could be done. Randy and I have been discussing questions like these lately: How do we transform our towns? We can transform our own yard into a garden farm, but what can we do beyond that? If we don't assume everyone has to be off-grid in suburbia, what other features are possible: commercial development, infill, replacing vacant lots with farms or parks, productive street trees, garage workshops, what else?

(Read: America Needs Strong Towns and Community, Not More Infrastructure)

Limitation: Large Families

I was also hoping there would be discussion of how to make retrosuburban life work for larger families. Most of the discussion of living situations in the behavioral field section focused on adults (married or single), or families with only one or two kids. While not surprising, given current family size trends, I read all those chapters with larger families in mind… and kept coming up short. For instance, Holmgren is big on walking and biking. Great! Except when you have young kids, and lots of them, it's often not practical. I have a friend who can't drive; I remember her explaining how she could take all her kids with her in the bicycle trailer, but then she didn't have any room for cargo.

Limitation: Climate

Holmgren is Australian in a temperate area prone to bushfires. He's very up front about it; the book is aimed at other Australians. If you live in a northern climate, like I do, just keep in mind when reading that you'll have to adapt the strategies and suggestions to include winter and no year-round growing season.

For instance, in the chapters on growing food, Holmgren suggests specific plants and trees. If you're not down under, I suggest asking local permaculture people and homesteaders what plants and trees would work well in your bioregion.

Some of the retrofits make less sense with several feet of snow to account for. E.g., the outdoor compost toilets. It's not going to be composting much when everything's frozen; you're probably not excited about an outhouse when it's below 0; and it's not practical for little kids who need to pee in the middle of the night.

Also, remember that a north-facing greenhouse in Australia is like a south-facing greenhouse in the northern hemisphere.

(Read: Why Idaho Needs a Victory Garden Tax Credit)

How we're applying retrosuburban principles

We live on a 0.17 acre suburban lot. It's in a great location: we're close to several public parks with open space and playgrounds, which means we don't have to reserve as much of our yard for playspace. (The kids quite happily play around and between the productive parts of the yard, anyway.) We like the convenience of being in town.

We're also all on board with home production and the home economy. We have a garden, and we're expanding the garden this year. We have chickens. We're getting bees this year. We like using our space optimally.

Retrosuburbia gave me some ideas for how to improve our yard, like the future addition of a greenhouse. I'll use the tips on building soil health. I don't think I'll bother harvesting rainfall—our seasons have big cold wet spells followed by big long dry spells, and you need some pretty big barrels to make that worthwhile.

Sounds great, but how do I start?

You don't have to go off-grid. You don't have to install solar panels or rain barrels or a compost toilet.

The simplest step is to start producing something at home. Sure: it can be producing energy from solar panels. Or producing herbs on your kitchen windowsill in a couple of pots. Or sourdough bread.

The first step is returning to home production.

(Read: The Farmer's Lament, a Poem)

How you can get the book

Overall: If you want to go off-grid in suburbia, this book is for you. If you're interested in permaculture, localism, resilience, sustainability—this book is also for you.

The best part: You can read Retrosuburbia right now! It's available online Or you can buy a hardcopy; I think that's worth it for the pictures, diagrams, ease of flipping between chapters.

Tutorial: How to Make an Easy Patchwork Peasant Skirt